They always come in threes.

First it was Jan-Michael Vincent, dead of a heart attack on February 10, at 73. Then, eleven days later, Peter Tork, 77, lost to cancer. And then, finally, Luke Perry, who died on March 4 after a stroke at the tragically young age of 52.

Another trio of celebrity deaths, another odd coincidence noted and then forgotten.

But there was more than fame linking these men, and more separating them than their causes of death. Each burst onto the national stage as a teen idol. Each flourished during a different decade, drawing millions of young fans.

And yet each promised something different to those admirers, and then saw their careers take different paths—partly due to their choices, and partly due to the choices the times they inhabited made for them.

Peter Tork, for example, emerged in 1966 while Beatlemania was still strong—but also at a time when the once-lovable moptops were singing about drugs and speaking out about Vietnam. The American entertainment industry yearned for a safer, cheaper version they could sell to advertiser:. Enter the pre-Fab Four, the made-up Monkees, squeaky-clean and ready for primetime.

It was a cast-for-TV quartet carefully built to Beatles blueprints, with Mike Nesmith taking the place of brainy John, Davey Jones playing cute Paul, Mickey Dolenz as a goofy Ringo. And if that left Tork to play fill-in for George, that was fine—although he didn’t have Harrison’s edge, he did have a serious interest in music, and a loose, hippie vibe.

Yet the manufactured madness of it finally overwhelmed Tork, who yearned to get back to Greenwich Village coffeehouses and low-key folk. He literally bought his freedom in 1969, using most of his savings to get out of his contract. Broke but happy, he returned to banjo playing, made some records, even taught high school. Occasionally, he’d reunite with his old bandmates on tour.

Being a teen idol had never set right with Tork. Yet for that innocent, flower-power era, he was perfect. Sweet and unthreatening, he was the sort of man even 11-year-old girls wanted to mother. Like other young stars of those groovy times—Bobby Sherman, Peter Noone—he seemed about as sexual as a puppy dog, a happy Lab in love beads.

Which is, of course, the purpose of a teen idol, to present awkward adolescents with an absolutely safe, and impossibly remote, fantasy figure. To give them a plastic Ken doll version of the boys they’re still too young, or scared, to date.

But fantasies change, and by the 1970s, rock’s sexual androgyny had begun to spread throughout pop culture. And young girls—and some young boys—picked up on it. Teen idols now needed to appeal to females and males, straights and gays. The call went out for boys with pouty lips who looked good in paisley shirts and faded jeans, and weren’t shy about shedding either.

It was a role that Jan-Michael Vincent was happy to fill, even dropping trou for “Buster and Billie.” With shaggy blonde hair, bright blue eyes and a torso chiseled by hours of California surfing, Vincent provided the perfect daydream for young teens. And, unlike the younger and even prettier David Cassidy, there was an edge to Vincent, a hint of surly danger.

Of course, the bad-boy rebel is just the puppy-dog innocent roughed up a bit—like a non-threatening kid brother, it appeals to his fans’ protective instincts. Yes, he’s dangerous, like a snarling beast with a thorn in its paw. But maybe you—and you alone—are special enough to save him. If you can just screw up your courage long enough to get near, to just win his trust…

Vincent’s wounded animal beauty kept his star bright for years, but then drugs and alcohol barged in and the rest was disaster, but in slow-motion, like one of those crash-test dummy videos.

There were three arrests for cocaine, two more for bar fights, several charges of spousal abuse, and too many automobile accidents to count. Piece by piece, Vincent faded away. He broke his neck in one car crash. An emergency intubation cost him much of his voice. Later, peripheral artery disease took most of his right leg.

When Vincent died in a North Carolina hospital, it took nearly a month before the press even noticed.

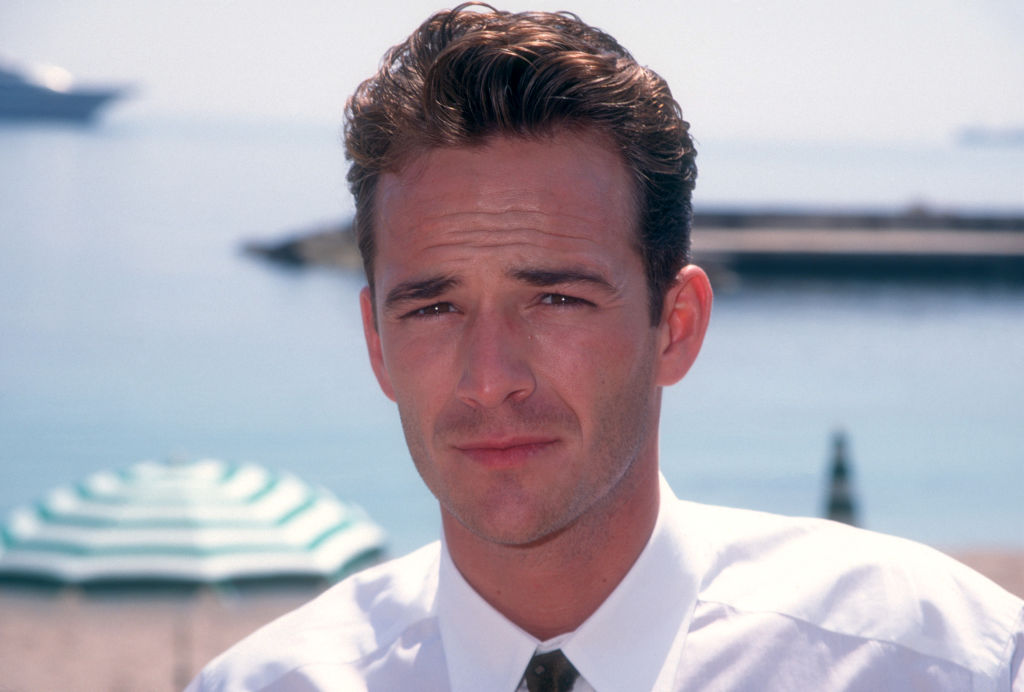

If Vincent was a kind of sad reversal of the old James Dean ethos—living fast, but dying old and leaving an ugly corpse—Luke Perry offered a different example. Perhaps, again, it was because of the era he served. Tork found fame during an age of optimism; Vincent, during one of hedonism. But Perry was made in—and maybe made for—the Irony Years.

It was a decade of snark and sarcasm, of air quotes and “As if!”—really, how could anyone take anything seriously in the ’90s? “Isn’t It Ironic?” Spy magazine asked on its March 1989 cover, detailing the new trend to treat everything as a joke. As usual, they were only slightly ahead of the curve.

And when the wave came, Fox’s Beverly Hills, 90210 rode it. Premiering in 1990, created by high-camp counsellor Aaron Spelling, it was a cliché that knew it was a cliché, buttering its soap-opera corn with lavish dollops of tongue-in-chic melodrama.

Of course, an ironic age demanded an ironic icon, and Perry obliged. The leather jacket, the sports car, the sideburns—it was hard to take the rich-but-brooding Dylan seriously. And Perry never demanded that audiences completely did. He let them indulge without commitment, or guilt, just like Dylan would. Which is why when the show finally ended—along with the decade—its fans only looked back at it with a sweet nostalgia.

Perry too, perhaps. Although he had left the series for a while, when other opportunities didn’t present themselves he returned to the old zip code without complaint. Once the party was over, he simply moved on, unworried by his own receding hairline and increasingly craggy features. He voiced cartoons. He played villains, and cowboys. He devoted himself to his children.

He died too young, of course. But at least he seemed to have lived without making too many mistakes.

Three different teen idols, three different decades, three different appeals, yet each filled the fantasy-figure role their era assigned him.

Of course, times were simpler then. Today, thanks to social media, teen idols are everywhere and nowhere at once. Who’s this year’s Shawn Mendes? Try asking, Who’s this month’s? But if you write his name down, be sure you use a pencil—there’ll be another one replacing him soon enough. These days, YouTube and Instagram squeeze them out like sausages from the Play-Doh Fun Factory, and they only last until the next click.

Which is why it’s fun to remember, for a moment, the teen idols of seasons past, the ones who came with a lame tie-in record album, and a huggable kissable poster and flirty covers on 16 magazine. Who lasted, at least, for a few, sickly-sweet, Love’s Baby Soft years. And who briefly sought to give apprehensive adolescents nothing more than someone to safely dream about—until they moved into the scary real world.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.