LeBron James will earn just over $33.2 million from the Cavaliers this season, trailing only Steph Curry (who collects roughly $34.6).

Not bad, but not Neymar.

The 26-year-old Brazilian soccer star’s salary from Paris Saint-Germain F.C. is $44.5 million. (It’s been reported that, with bonuses, he could earn up to $350 million over five years.) But wait, there’s more. PSG paid $263 million for the privilege of acquiring him from Barcelona F.C. (Far from being grateful for the cash, Barcelona vice-president Jordi Mestre slammed Neymar for having “played cat and mouse with us.” Mestre blamed him for driving up the value of his replacements: “What Neymar’s behavior created was the market inflation. We would have saved a lot of money and a lot of media noise.”)

In total: PSG will pay somewhere from just under $500 million to potentially over $600 million for the services of a single player for five years. Even if Neymar continues to bank “only” $44.5 million, that breaks down to $97.1 million per year. (The entire Golden State Warriors roster collects $137.5 million this season.)

With the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) acknowledging they are considering a salary cap, it’s worth asking: Is the Neymar haul as high as the water can rise?

Stefan Szymanski believes there’s little reason to think so: “Transfer fees have risen inexorably at an annual compound rate on the order of 10 to 15 percent fairly steadily for 130 years.”

In case you didn’t guess from that last sentence, Szymanski is an economist. He serves as the Stephen J. Galetti Collegiate Professor of Sport Management at the University of Michigan and his books include Soccernomics (co-authored with Simon Kuper, it just received a 2018 World Cup Edition), It’s Football, Not Soccer (And Vice Versa) (co-authored with Silke-Maria Weineck) and Money and Soccer.

Szymanski says the explosion in transfer fees and salaries for the beautiful game only makes sense: “If you go back to 1990, the total revenue generated by European professional soccer at all levels was less than any one of the three major sports at that time: NFL, baseball, the NBA.”

Now? “The combined revenues of European professional soccer is larger than all three of those leagues combined.”

Beyond this, there aren’t just multiple teams that would love to have a player like Neymar, but multiple leagues. (The big four are typically cited as England’s Premier League, Germany’s Bundesliga, Spain’s La Liga and Italy’s Serie A—it’s proof of the depth of job opportunities that Neymar can generate hundreds of millions while skipping that quartet for France’s Ligue 1.)

These leagues don’t handle things the way we do in American sports: “In the United States, you have a monopoly, where leagues don’t see competition from rival leagues.”

Athletes in America typically are drafted by a team, play out a rookie contract and only then get to sell themselves as free agents. (Albeit with salary caps and other rules that limit how much they can be paid.)

Soccer lets you open yourself up to takers from all over the world.

Yet while soccer’s free market gives, it taketh too.

“Unionization in soccer is a much less effective than it is in the United States,” says Szymanski. “One manifestation of that is the transfer system itself.”

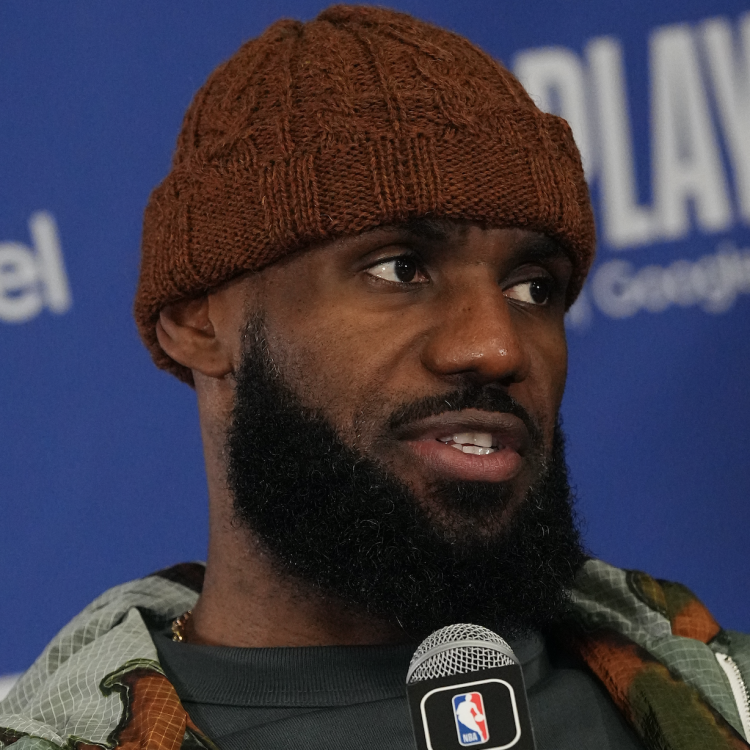

Let’s go back to LeBron. Naturally, he commands the top salary on his Cleveland Cavaliers. His teammates, however, do quite well for themselves. Five earn over $11 million: Jordan Clarkson ($11.5), J.R. Smith ($13.7), Tristan Thompson ($16.4), George Hill ($20) and Kevin Love ($22.6).

Between them, Thompson and Hill make $36.4 million, topping LeBron’s $33.2. This is despite LeBron being more important to his team than they are combined. (That is a simple statement of fact: Even if you add Tristan and George’s stats together, King James still generates more points, assists and steals per game and nearly as many rebounds and blocks.)

Szymanski says a reasonable argument can be made that LeBron is underpaid, but even Thompson and Hill’s agents would struggle to make the same claim for them: “If there’s redistribution in the NBA, the redistribution is really from the most talented players to the least talented players. That’s in some ways the price you pay in the union system to get your price out of the owners.”

Yet even if the union drags LeBron down in this way, it builds him up in another. When LeBron returned to Cleveland as a free agent, the money went to him, not to the Miami Heat. Neymar, however, saw much of the PSG’s payout go to his former team. (This phenomenon isn’t limited to Europe or soccer: When Shohei Ohtani came to the United States, he collected a $2.3 million bonus and a salary of $545,000. His franchise back in Japan pocketed $20 million.)

At this point, it’s worth looking at the first massive transfer of Neymar’s career, as his arrival in Barcelona somehow managed to be even more controversial than his departure. Neymar was a star for the Brazilian club Santos when he decided it was time for a European payday, inspiring a frenzied courtship by the continent’s top teams. Barcelona won. In 2013, a deal was announced for 57 million Euros ($68.9 million). It was later revealed that Neymar’s actual price, however, exceeded 100 million Euros ($120.8 million). Quite simply, Neymar’s parents demanded—and received—over $40 million in payments, arguing that they owned the majority of a company that held the rights to their son.

Transfer fees often serve a function similar to the one carried out by unions in the U.S.: They take some money from stars, but they help other players get paid. Transfer fees usually go to buying more players: “The clubs themselves generally don’t make large profits. Barcelona is not even a for-profit business. It’s a members association. The only way it can spend the money is on buying more players. In some ways, that [Neymar] money is going to be redistributed to be spent on less talented players.”

(Barcelona has already spent the Neymar dividend and then some, signing Ousmane Dembele from Borussia Dortmund for up to $177.5 million and Philippe Coutinho from Liverpool for as much as $192.7 million.)

How high can these fees go? Massive as his paychecks might be, Neymar isn’t yet the world’s most valuable player. That would be his former Barcelona teammate, Lionel Messi. (Ronaldo fans should note Cristiano is 33 and Lionel only 30—time’s on the Argentine’s side.)

The Flea’s buyout clause is 700 million Euros ($845.5 million), reminding King James he pays a massive price for the privilege of using his hands.

Below, Neymar discovers the pleasures of having the details of your finances shared with the entire world as Bayern fans hurl fake money at him.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.