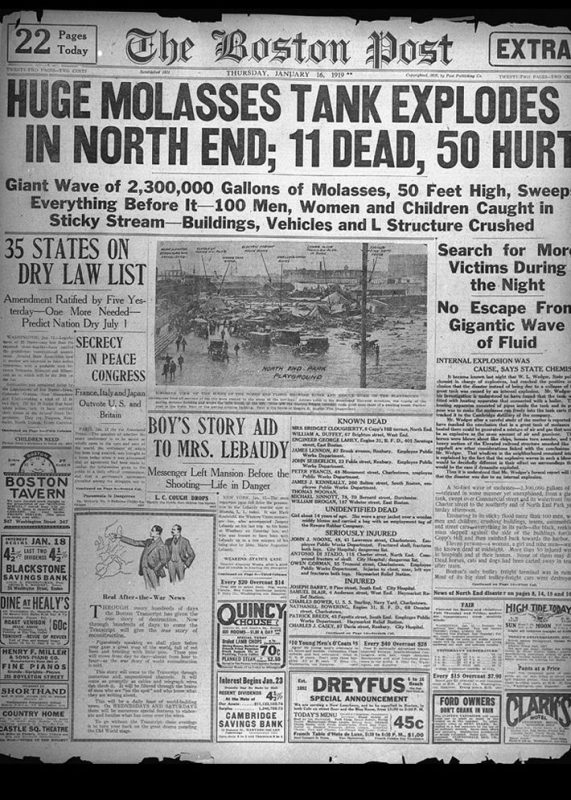

One of the strangest episodes in American history occurred in 1919, when a 40-foot wave of molasses syrup flooded the streets of Boston, killing 21 people and injuring 150. How does something like that even happen?

A team of scientists from Harvard had this exact same question, and presented some helpful research to the American Physical Society earlier this month; they contend that the molasses’ reaction to the notorious Boston winter cold is what made it so deadly.

Upon arriving in Boston, the molasses was heated and kept in a storage tank near the waterfront. The tank (holding 2.3 million gallons of the sweet stuff) burst two days later, and because the molasses was warmer than the surrounding air, it moved fast enough to do a lot of damage before thickening, which complicated rescue efforts.

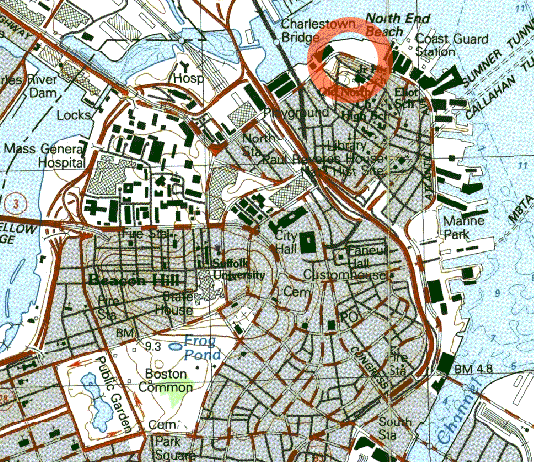

The whole thing sounds absurd, but pictures from the disaster don’t lie. Quite a few buildings in the city’s North End, including a firehouse, were destroyed.

The Harvard researchers experimented with corn syrup in a walk-in freezer as a model for the conditions surrounding the molasses, and found that despite its reputation for being thick and slow, the substance moves very quickly in those conditions. When they applied their data to a projection of a map of the North End, their results matched eyewitness accounts from the flood.

“It’s an interesting result,” aerospace engineer Nicole Sharp told The New York Times. “It’s something that wasn’t possible back then. Nobody had worked out those actual equations until decades after the accident.”

As for the holding tank, recent engineering research suggests that it was poorly designed. It was originally thought that the tank had somehow exploded, but structural engineer Ronald Mayville told The Boston Globe that the tank was too brittle and its walls were too thin, making it unable to contain that amount of molasses as it responded to atmospheric changes.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.