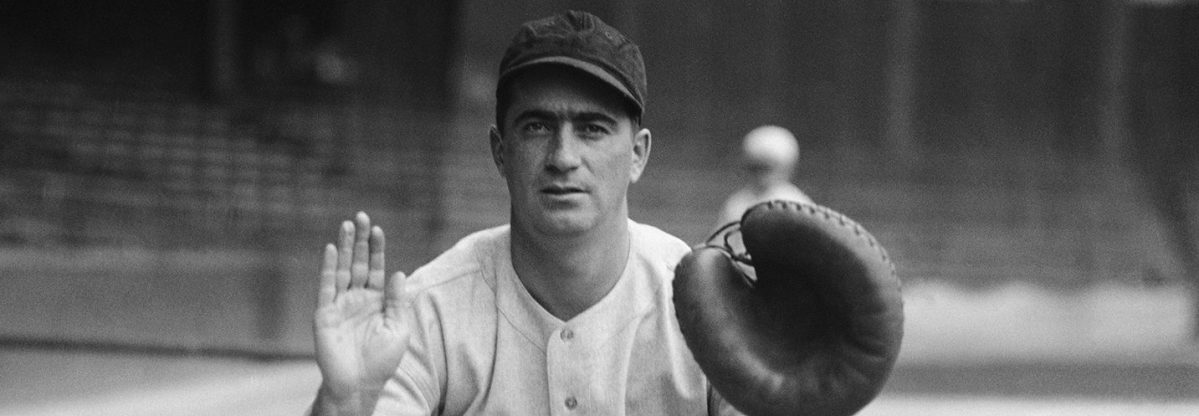

In 1933, the Goudey bubble-gum company released a set of baseball cards, featuring a panoply of future baseball Hall of Famers, including Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Jimmy Foxx. The set also featured some lesser-known ball players, guys that kids of the day wouldn’t have likely paid much attention to or swapped away. One such card? No. 158, which featured backup catcher Morris “Moe” Berg.

Back then, baseball cards weren’t valuable collector’s items like they are today. They were more the objects of children’s games and used by companies like Goudey, as miniature billboards to bubble gum, candy and tobacco.

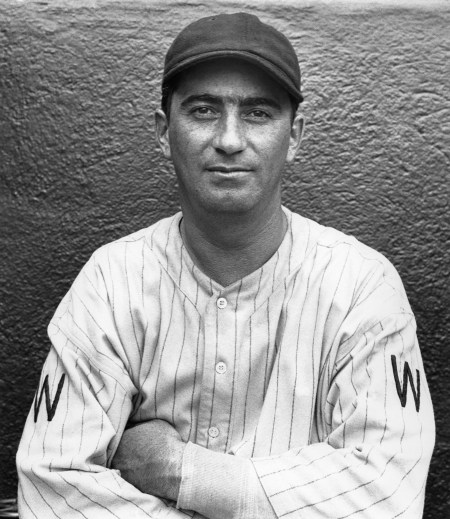

On the card, Berg is wearing a Washington Senators uniform. Despite being peppered with Hall of Fame talent such as Walter Johnson, Joe Cronin, and Heinie Manush, the D.C.-based franchise, at the time, had many more memorable losing seasons than it did winning ones.

There’s an irony in the fact that Berg was representing the U.S. capital that season: Just a decade later, during World War II, he spied for the U.S. government and was involved in one of the war’s most dangerous missions.

Born in Harlem to Jewish parents in 1902, Berg was a natural athlete, excelling at both baseball and academics in high school. After graduating, he enrolled at New York University, transferring after just one year to Princeton University, where he’d split playing for the university baseball team with coursework in modern languages. He graduated magna cum laude in 1923.

Instead of going on to get a master’s degree in linguistics or find work as an interpreter, Berg signed with the Brooklyn Robins—later, the Dodgers—the same year he graduated college. It kicked off a baseball career that can only be described as supremely mediocre—and at times, downright terrible. Berg pivoted from a promising shotgun-armed infielder to a professional bench-warming, third-string catcher. He played a total of 15 years for teams including the aforementioned Senators, Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians and Boston Red Sox. He ended his career in 1939 with the Red Sox and then spent two years as a coach there.

Baseball didn’t quell Berg’s insatiable quest for knowledge. “The Professor,” as New York Times sportswriter John Kieran dubbed him, was a voracious reader, reportedly spending three hours a day digesting some national and international newspapers. In the fall of ’23-’24, Berg traveled to Paris and studied French at the Sorbonne. (Berg was reportedly fluent in as many as 13 languages.) While playing for the White Sox in the middle to the late ’20s, he managed to earn a degree from Columbia Law School concurrently. He graduated in 1930—a year he played just 20 games and hit a miserable .115—joining a law firm as well.

Then, two years later, Major League Baseball sent him abroad as part of a three-man ambassadorial team to demonstrate America’s pastime to the Japanese. (Berg would famously teach himself how to speak Japanese on the boat ride over from Seattle, acting as his team’s unofficial translator for the rest of the trip.) In ’34, he would follow up his first trip to Japan with a better-remembered jaunt that included hitting heavyweights like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

In ’39, Berg would fortuitously tell New York Times sportswriter Arthur Daley: “Europe is in flames, withering from a fire set by Hitler. All over that continent, men, women, and children are dying. And what am I doing? I’m sitting in the bullpen telling jokes to the relief pitchers.”

Even with his mind abroad—and as a Jewish man, a much closer connection to the horrors that were taking place there—Berg even tried his hand at writing. In September ’41, just three months before the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor, hurtling America into World War II, Berg landed a byline in the prestigious Atlantic Monthly. He penned a hyper-smart, eight-page feature entitled, “Pitchers and Catchers,” in which he attempted to explain the meaning of baseball.

All that before he became a spy.

In actuality, it was Berg’s second trip to Japan in ’34, that gave him his initial taste for spy-craft. While there, he reportedly talked his way—in fluent Japanese, of course—into Tokyo’s St. Luke’s International Hospital disguised in a black kimono, with a primitive movie camera strapped to his body; snuck up to the roof; and shot footage of the Japanese city below. Although it’s never been confirmed, it’s been reported that a decade later, U.S. General Jimmy Doolittle—the famed airman and Medal of Honor recipient—had his men view the tape before unleashing a fiery aerial assault on the Japanese city.

First serving the U.S. cause in ’42, Berg was appointed a special advisor to Nelson A. Rockefeller’s Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, where he worked as a paramilitary officer, parachuting into hot-spots like Yugoslavia and conducting intelligence sweeps of resistance fighters, per declassified documents from the Central Intelligence Agency.

Then in the summer of ’43, he filled out an application for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a predecessor of the modern Central Intelligence Agency. The position would change his life—and arguably, the tempo of the war.

Before being given his mission, Berg would’ve had to take part in a two- to four-week training session, as is noted in declassified CIA documents. Locations like Catoctin Mountain Park in Maryland and Prince William Forest Park in Virginia, both national parks—and even the Congressional Country Club—served as training grounds. In the national parks, for instance, trainees were instructed on how to engage in knife-fights and other hand-to-hand combat; provided combat scenarios, which involved busting down doors and pumping out live rounds; taught secret codes and ciphers; and were shown how to make and disarm booby traps.

Once accepted into the OSS, Berg worked under the tutelage of intelligence officer Robert Furman, traveling to hot-spots like Norway, Italy, and Germany, investigating a number of Nazi scientists. That included the head of its atomic program, Werner Heisenberg, whom Berg was ordered to assassinate if he deduced that the Nazis had a detonatable A-bomb. At one point, it looked like they might. Per CIA archives, Berg reported to his handlers in January ’44 that a Belgian company in the Congo had sold 700 tons of uranium ore to the Nazis, delivering it to Duisburg, Germany (a port city that was a constant target of Allied bombers). It was believed that the tonnage, along with additional Nazi uranium stockpiles in Czechoslovakia, might be enough for the Third Reich to build an atomic bomb. But by November of that year, U.S. intelligence (and in turn, Berg) had confirmed that the Nazis neither had a bomb nor the capability to make one. Berg aborted his mission.

Of course, we know now how World War II ended: With the U.S. detonating its own pair of atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. But any number of scenarios could’ve played out had Berg not been at the right place at the right time.

In 1972, the year he died at age 70, Berg quipped:

“Maybe I’m not in the Cooperstown Baseball Hall of Fame like so many of my baseball buddies, but I’m happy I had the chance to play pro ball and am especially proud of my contributions to my country. Perhaps I could not hit like Babe Ruth, but I spoke more languages than he did.”

Speaking of the Hall of Fame, while Berg did miss enshrinement by a long shot, the museum confirmed to RCLife that it holds some of Berg’s items in its permanent collection, including his Senators uniform—and Medal of Freedom, an honor bestowed upon him in 1945, but which he flatly rejected. (Read Nicholas Dawidoff’s The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg for more on the whys and wherefores; a film based on the book, starring Paul Rudd, is expected some time this year.)

And that ’33 Goudey baseball card we mentioned above? Not only is it one of the more sought-after cards among collectors today, but the CIA has a copy of it housed within its archives.

Not bad for a career .243 hitter.

Unless otherwise noted or cited, all of the information reported in this story comes directly from and courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Moe Berg Clipping File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.