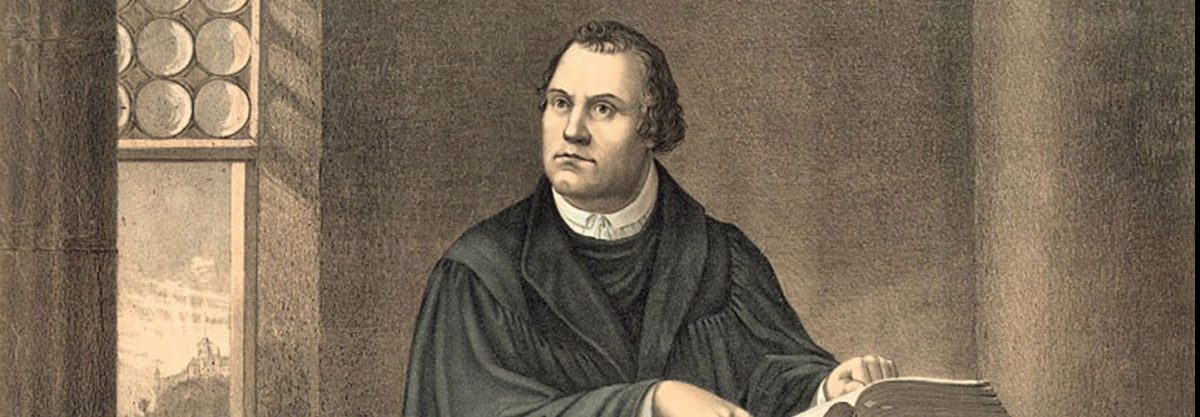

In a new article, the Wall Street Journal calls Martin Luther an “unlikely revolutionary for human freedom” — and details the ways that his teachings, personal experiences and writings helped create the foundation upon which our modern democracy and understanding of human rights stands upon.

As someone who hated spiritual elitism — the WSJ points out that he was born into a German peasant family in the fifteenth century — Luther wanted to create a “priesthood of all believers,” banishing archaic hierarchies within the church that pushed out regular people. In 1520 he asserted in “The Babylonian Captivity of the Church’ that “pretentious lives, lived under vows are more hostile to faith than anything else can be.”

He also aimed to dignify work of all kinds, no matter what it was: “A shoemaker, a smith, a farmer, each has his manual occupation and work; and, yet, at the same time, all are eligible to act as priests and bishops,” Luther wrote. He also went on to cut away at legal policies that protected those who held church offices, simply because of their standing in society.

He wrote: “It is intolerable that in canon law, the freedom, person, and goods of the clergy should be given this exemption, as if the laymen were not exactly as spiritual, and as good Christians, as they, or did not equally belong to the church.”

This argument of equal treatment under the law went on to become just one component of what the WSJ describes as a “core tent of liberal democracy.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.