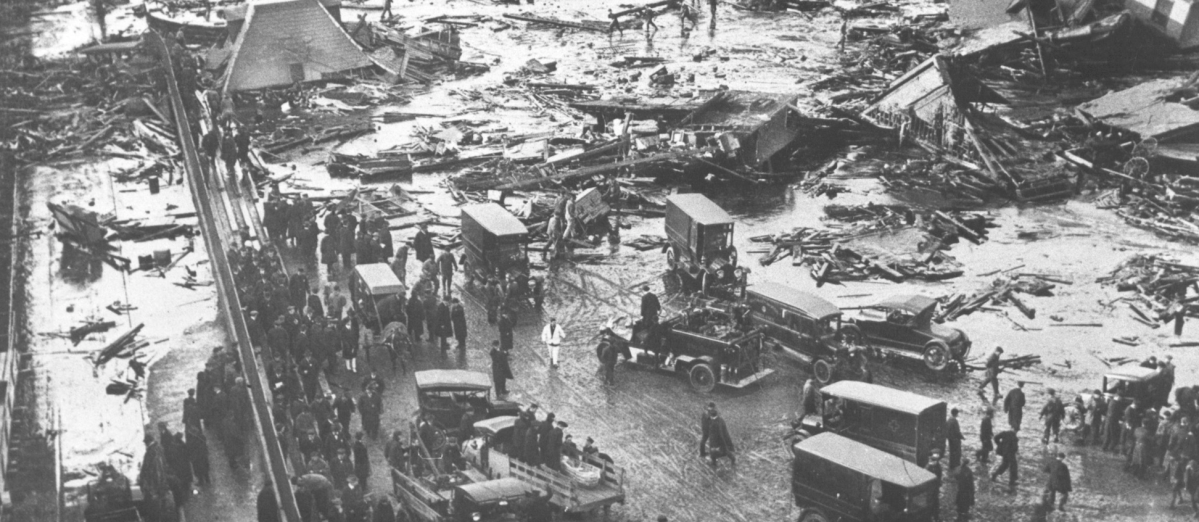

A century ago, a deadly wave hit the city of Boston, killing dogs, horses, and 21 people as well as injuring 150 more in its path of destruction.

But it wasn’t a tsunami of water, but of syrup.

Specifically, the wave that swept through the cobblestone streets of the city’s North End on January 15, 1919, was 2.3 million gallons of sugary molasses, according to The Boston Globe.

The disaster was unleashed when a giant storage tank—made from the same type of steel as the Titanic—in the city’s North End ruptured around lunchtime. Almost immediately, the Great Molasses Flood of 1919 was 25 feet high and 100 yards wide when it began sweeping down Commercial Street.

Propelled by its own weight, the wave was the complete opposite of being slow as molasses. In fact, its speed approached 35 miles per hour, which caused the buildings it impacted—like the Engine 31 firehouse—to “cringe up as though they were made of pasteboard.”

A non-Newtonian fluid like toothpaste and ketchup, molasses is thick and goopy when at rest but can flow quickly and powerfully once stress or shear forces are applied. As it slows, it becomes more viscous again.

Had the collapse happened in spring, summer, or fall, the wave may not have killed anyone. However, thanks to the wintry temperatures, the warm wave thickened as it cooled and essentially turned into a mass of mobile cement.

Bystanders in the wave’s path had no chance to outrun it and, once caught inside of it, only got themselves more stuck while struggling to free themselves. Rescuers attempting to get to the victims had similar problems.

As a result, about half of the victims were crushed by the wave or either drowned or suffocated in the gelatinous substance. The other half of the victims died from injuries and infections in the weeks following the flood, according to Scientific American.

Amid the fallout of the disaster, about 120 lawsuits involving victims of the incident were rolled into a class-action suit against the owner of the storage tank, United States Industrial Alcohol, arguing that the company had been negligent by building a holding tank which was too thin to safely hold its contents.

In a landmark ruling following an investigation which lasted six years and featured testimony from witnesses including explosives experts, flood survivors, and USIA employees, Massachusetts state auditor Colonel Hugh Ogden ruled USIA was fully at fault for the incident, and forced the company to pay out nearly $7 million in settlements (about $106,583,696 today with inflation) to flood victims and their families.

In addition to the amount of the awarded damages, the ruling was also noteworthy because it was one of the first times a corporation was held accountable for trying to maximize production and minimize cost during construction.

Following the verdict, Massachusetts and many other states responded by passing laws that changed the way government interacted with business.

“All the building construction standards that we take for granted today – that architects need to show their work, that engineers need to sign and seal their plans, that building inspectors need to come out and inspect jobs – all came about because of the great Boston Molasses Flood,” Stephen Puleo, the author of Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, told RealClearLife. “So, very important long-term ramifications of the flood.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.