In the summer of 1918, as World War I raged on, the City of Brotherly Love organized a massive parade to bolster morale and support the war efforts. Philadelphia prepared a procession including marching bands, Boy Scouts, women’s auxiliaries, and uniformed troops to promote Liberty Loans, which were government bonds issued to pay for the war. The day would end with a concert by John Philip Sousa.

About 200,000 people lined up on Broad Street. But then, disaster struck. Philadelphians were exposed en masse to a lethal contagion called the “Spanish Flu,” which was a misnomer created earlier in 1918 when the first published reports of a mysterious epidemic emerged from a wire service in Madrid.

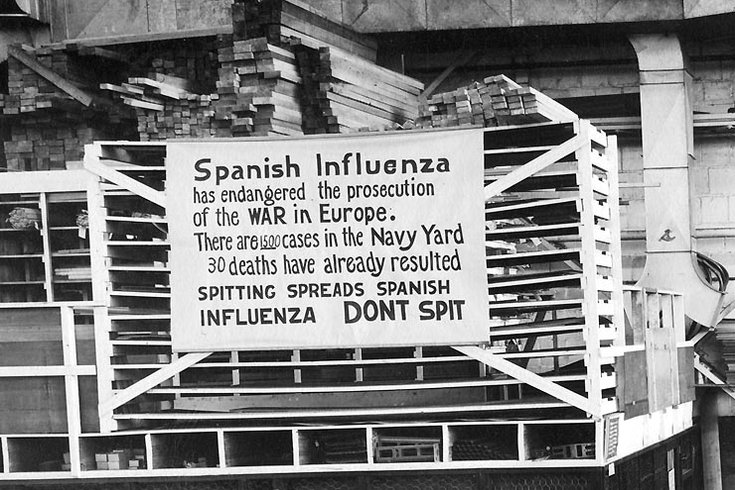

Two days after the parade, the city’s public health director Wilmer Krusen, said: “The epidemic is now present in the civilian population and is assuming the type found in naval stations and cantonments [army camps].” During the planning of the parade, he had ignored the growing concerns of medical experts, even though a deadly outbreak raged on nearby military bases.

Smithsonian Magazine writes that within 72 hours of the parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s 31 hospitals was filled. By October 5, about 2,600 people in the city had died from the flu or its complications and a week later, that number rose to more than 4,500. The city was essentially shut down. After the epidemic, Philadelphia officially reorganized its public health department.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.