“A good big man always beats a good little man.”—Boxing adage

The Basketball Association of America (soon to be the NBA) started in 1946. By 1948, they had their first icon and he was, in every sense, a massive presence. At 6’10” and 245 pounds, George Mikan simply overwhelmed opponents, inspiring rule changes to try to limit his dominance. Mr. Basketball only played seven seasons but led the NBA in scoring three times and won five titles for the Minneapolis Lakers.

By the time Mikan passed in 2005, much about the NBA had changed. (For one, his Lakers had moved to L.A.) He poked fun at how far the game had come in an ESPN ad.

But through all those decades, there was a common thread that if you wanted to contend, you got a big man. 6’10” Bill Russell won 11 titles and 7’2” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar took six while combining for 11 MVP Awards. Big men also shredded the stat sheet. Wilt Chamberlain (7’1”, 276) and Shaquille O’Neal (7’1”, 326) led the NBA in field goal percentage a total of 19 times and in scoring nine. The latter figure might have been higher if not for each being a historically bad free throw shooter. (Chamberlain made only 51.1% for his career, including a phase when he attempted them underhand.)

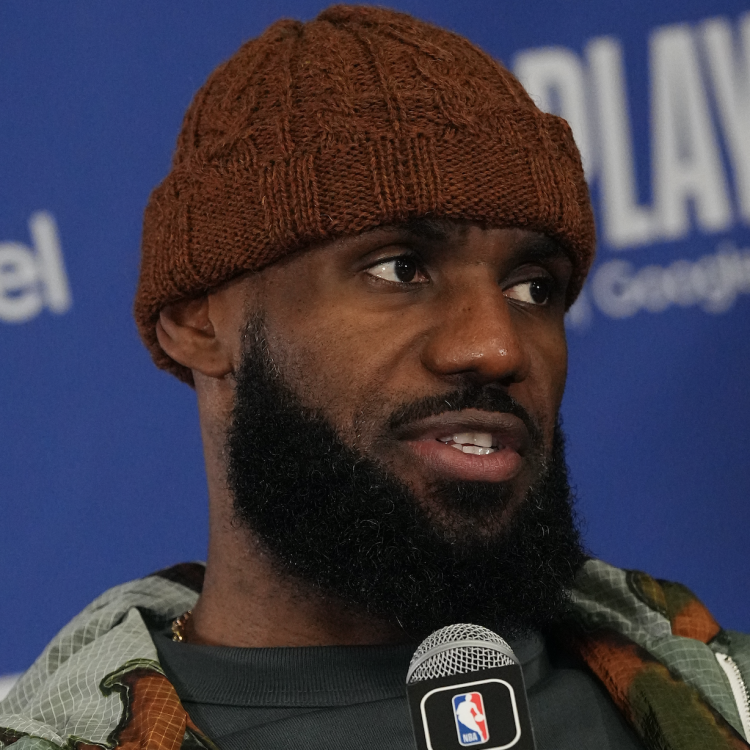

Today, Mr. Basketball might barely recognize the NBA. To start, Mikan would have to duck way down to see it. The last three MVPs went to a player listed at 6’3”: two for Steph Curry and one for Russell Westbrook. During that same period, Westbrook led the NBA in scoring twice and Curry once. This year’s trophy will almost certainly go to the new scoring champ, Houston Rocket James Harden. At 6’5”, “The Beard” is significantly shorter than James Comey.

Quite simply, even the biggest player can be cut down to size by an opponent who’s skilled, speedy and—above all—plays in a league willing to make radical changes to help the little guy. (Chamberlain used to muse, “No one roots for Goliath.” Count the National Basketball Association as firmly in David’s corner.)

The NBA may have started decades after Major League Baseball was up and running, but it’s evolved far more. When the cartoonist-turned-pitching guru Michael Witte spoke to RCL, he noted you could look at a “flip book of ‘Three-Finger Brown’ produced in 1906 or so” and witness pitching mechanics that still apply to top hurlers today.

Basketball is largely unrecognizable from its origins. In 1963, Celtic Hall of Fame point guard Bob Cousy declared, “I think the jump shot is the worst thing that has happened to basketball in ten years.” His reasoning: “Any time you can do something on the ground, it’s better.” (Yes, this does sound like the voiceover to the least exciting Air Jordan commercial ever.) Cousy’s highlights reveal a player with a gift for bold passes… but one who remained decidedly earthbound.

Today, the NBA is filled with jumpers, dunks and small players generally imposing their will on the giants. Here are the three key ways the NBA gave little men a leg up:

Make the Big Man Move Away. Baskets come no easier than when a large person being guarded by a tiny one gets the ball next to the hoop and lays it in. (Flashback to childhood and your dad toying with you on the driveway.) The NBA did its best to minimize these opportunities, with the offensive three-second rule limiting the amount of time a big man can wait for the ball in the lane, right next to the basket.

Then the NBA did more. During the 1950s, they widened the lane from six to 12 feet. (This is generally credited as an attempt to slow down the Mikan Express.)

And when Wilt started regularly scoring 50 and generally putting up numbers Mikan could only dream about, the lane expanded again to 16.

Now a big man either needed teammates skilled enough to deliver the ball in the window of time between his moving into position and the three-second count expiring or had to post up farther away from the hoop.

Did it stop the big man from scoring? As Wilt and Shaq so ably proved, it did not. Did it make him work harder for it? (Or at least move around more than he’d like?) Absolutely.

Then the rules offered a reward for those willing to stay outside.

Plus One. Before the 1979-80 season, a three-point line was established. (22 feet in the corners extending to 23 feet, nine inches at the top of the key.) And nothing happened.

That first season, teams averaged just 2.8 attempts and .8 makes (for 2.4 points per game) while shooting 28%. (The overall field goal percentage was .481.) Brian Taylor led the NBA with 90 makes over 78 games.

The second year things got worse: 2 attempts, .5 makes, .245 shooting percentage and Mike Bratz pacing the league with 57 threes.

But there was no denying the math:

-If you shoot 10 two-pointers and make half of them, that’s 10 points.

-If you shoot 10 three-pointers and make a mere 40 percent, it adds up to 12.

This season, NBA teams averaged 29 attempts, 10.5 makes—31.5 points per game—and shot at a .362 clip, not to mention the overall field goal percentage dipped to .460. (Houston attempted 42.3 threes a night and made 15.3.)

In his MVP season of 2015-16, Steph Curry shot .454 from three-point range and hit 402 of 886 attempts. (This was the equivalent of shooting 73% on twos.)

So the NBA made it harder for inside players while rewarding outsiders. But the game’s greats might still be a little bigger if not for this last tweak.

Watch the Hands. Ahead of the 1994-95 season, the Washington Post reported: “Referees have been told to vigorously enforce the hand-checking rule this season. Hand-checking — in which a defender impedes the dribbler’s progress by placing his hand on the offensive player’s hip — will be eliminated from the end line in the backcourt to the opposite foul line.” It noted the “rule should provide offensive players with greater freedom of movement and subsequently, more scoring.”

While the NBA continually refines just what hand checking entails and how aggressively referees should police it, there’s no question this benefited players who possess more speed than strength.

Take the 2006 NBA Finals, when 6’4” Dwyane Wade became literally unstoppable. He averaged 34.7 points during the six-game win over the Dallas Mavericks. This included a staggering 97 free-throw attempts: more than 16 per game. (By comparison, the Mavericks’ entire 13-man roster shot 155 of them—the disparity was so big there were rumors Dallas owner Mark Cuban hired a former FBI agent to determine if the officials actually fixed the series.)

It all comes together to create an NBA where size is largely neutralized as an advantage on offense. Consider what it means to defend 6’5” Harden and his backcourt mate Chris Paul (6′ flat):

-If you give them space when they bring the ball up the floor, they can take the three. (Back in the 1970s, those would have just been unusually difficult twos.)

-If you play them close, they drive to the hoop and you likely get called for a foul. (Until the 1990s, when defending someone with a speed advantage, you could literally reach out and slow them down.)

-If they just blow by you and take it the hoop, it’ll probably be a clear path because the three-second rule keeps bigs from hanging out in the paint.

Oh, and there were measures specifically aimed at eliminating flagrant fouls from the game. That means Curry and his 190 pounds will likely never experience how Detroit’s Bad Boys “defended” Jordan.

It all adds up a golden age for the little man. (No wonder the Rockets can put up 50 points in a quarter.)

Indeed, it’s so golden the big men have decided if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.

Brand New Bigs

In 2011, the Dallas Mavericks rematched Miami in the Finals. This time the Mavs came out on top. Wade found himself outplayed by Dirk Nowitzki. While a seven-footer, Nowitzki relied largely on his shooting touch. The Finals MVP even made seven threes as Dallas won their first title. (To put this figure in perspective, Shaq made a grand total of one three over 19 seasons.)

Another towering forward took notice of the Germanator’s success. When the Warriors won the 2017 Finals in five, Kevin Durant made 18 threes in just 38 attempts.

Or look at 6’11 Buck Giannis Antetokounmpo. The Greek Freak is often the tallest player on the court and frequently the fastest one too. (See below.)

Ditto for 6’10” 76er rookie Ben Simmons.

Quite simply, they increasingly do everything the little guys can… and they’re huge.

Even if the NBA skill positions don’t go all supersized, there’s reason to think the smaller stars may experience a clampdown. As Celtic legend Red Auerbach observed: “Basketball is like war in that offensive weapons are developed first, and it always takes a while for the defense to catch up.”

Until NBA defenses get up to speed, enjoy the show.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.