As much of the political world was riveted on Wednesday by the public Congressional testimony of Michael Cohen, former lawyer to President Donald Trump, another relatively little-noticed hearing on Capitol Hill dealt with another thorny issue: an exotic, yet potentially catastrophic threat to America’s electrical grid – from space.

At least, that was half of the discussion. The hearing, a roundtable organized by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, covered two topics: electromagnetic pulses (EMPs) and geomagnetic disturbances (GMDs).

You might have heard of EMPs. They are, according to the Department of Energy, “intense pulses of electromagnetic energy” that can result from natural causes but are more generally known as side effects of nuclear weapons.

As the film “Ocean’s 11” described one, an EMP is a nuclear bomb, “now but without the bomb.”

“See when a nuclear weapon detonates, it unleashes an electromagnetic pulse which shuts down any power source within its blast radius,” Don Cheadle’s Basher helpfully explains.

That’s a fairly accurate description and the U.S. government for years has been studying the potential for adversaries to use EMPs from, say, a high-altitude nuclear blast to knock out large portions of America’s electrical grid. The good news, according to Department of Homeland Security’s Brian Harrell who testified before the Senate committee, is that the U.S. intelligence community currently assesses there is no “specific, credible information indicating that there is an imminent threat to critical infrastructure from an EMP attack.”

But then there’s the threat the intelligence community can’t reliably predict: GMDs.

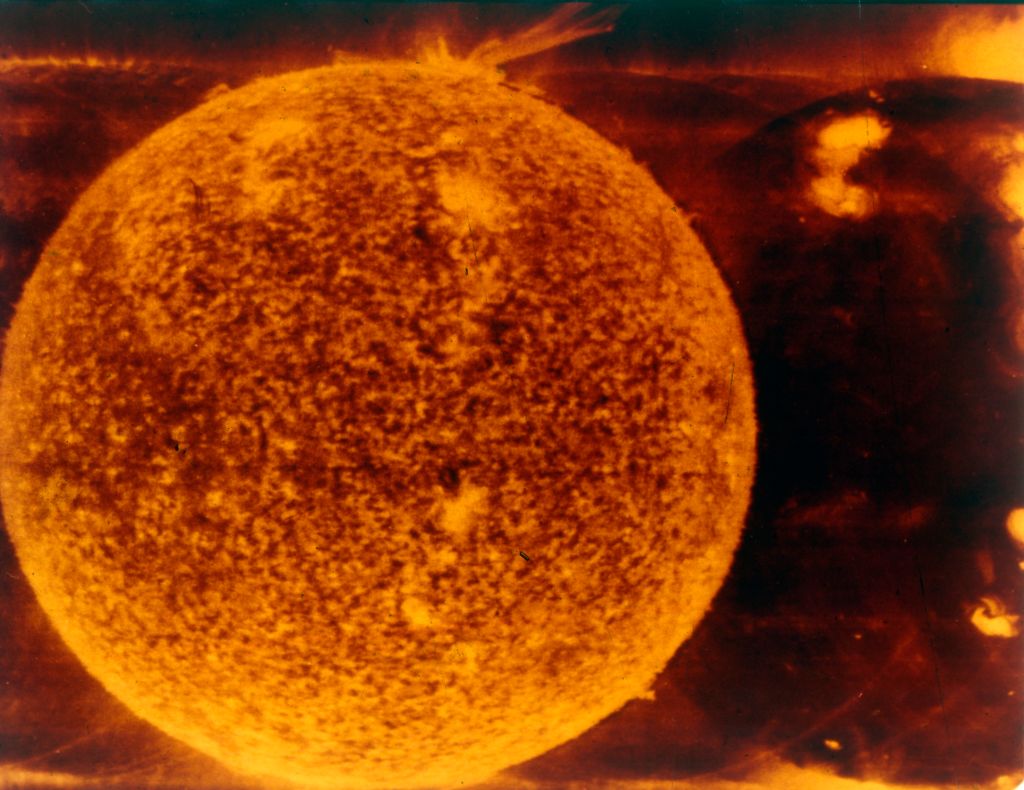

“A geomagnetic disturbance (GMD) or solar storm occurs when the magnetic cloud, called a coronal mass ejection, that is emitted from the sun as part of a solar eruption collides with the Earth’s shielding magnetic field,” Randy Horton, senior program manager at the Electric Power Research Institute and another panelist, said. “This collision generates currents in the magnetosphere and ionosphere of the Earth’s outer atmosphere which in turn induces GIC [geomagnetically induced current] in transmission lines and transformer windings at the Earth’s surface.”

Essentially: When the sun burps, it could shut out the lights back home. The events can last for several days, Horton said.

It’s not a new phenomenon.

In March 1989 a geomagnetic storm and the resulting “GMD-related harmonics” caused a blackout for the entirety of the Canadian province of Quebec.

“On Friday March 10, 1989 astronomers witnessed a powerful explosion on the sun,” a NASA account says. “Within minutes, tangled magnetic forces on the sun had released a billion-ton cloud of gas. It was like the energy of thousands of nuclear bombs exploding at the same time. The storm cloud rushed out from the sun, straight towards Earth, at a million miles an hour.”

Two days later a “vast cloud of solar plasma (a gas of electrically charged particles) finally struck Earth’s magnetic field.”

Hours after that the electrical currents created by the storm “found a weakness” in Quebec’s power grid and created a 12-hour blackout for millions of people.

And that storm was not nearly as powerful as another event from 1921 – well before the U.S. was as wired as it is today, according to a study prepared for the government’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory. That storm affected electrical power from Sweden to Pittsburg.

So what’s do be done?

The name of the game, according to the Senate witnesses, is to try and harden infrastructure against EMP/GMD flares and prepare for what to do when that’s not enough.

The federal government has already set standards for so-called “Bulk-Power Systems” that require transmission-owning electric companies to “assess and analyze their transmission systems under a severe 1-in-100-year GMD benchmark planning event,” according to Scott Aaronson, vice president of security and preparedness at the Edison Electric Institute.

But Harrell, the DHS official at the Senate hearing, said the administration is still figuring out an implementation plan to prepare the nation’s infrastructure for a major EMP/GMD incident, though they’re moving in that direction.

Another witness, Director Joseph McClelland of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, said some entities within the U.S., as well as several other nations, were already taking steps like “EMP hardening of power control centers and substation control buildings.”

“But,” he said, “much work remains.”

In the meantime, scientists will be doing what children everywhere are told not to do: staring at the sun and waiting.

“Unlike EMP attacks that are dependent upon the capability and intent of an attacker,” McClelland said, “GMD disturbances are inevitable with only the timing and magnitude subject to variability.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.