Comfort zones aren’t actually all they’re cracked up to be. Consider filmmaker Steve McQueen, who stepped out of his and discovered a whole new sweet spot.

The director of three serious, male-fronted and critically-acclaimed dramas starring Michael Fassbender — Hunger (2008), Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave, the 2014 Best Picture winner – McQueen has made a tidal shift in his latest film, Widows, out Friday.

Working from a script co-written by Gone Girl‘s Gillian Flynn, McQueen puts a quartet of women at the center of his latest, audience-friendly and exuberant thriller. And his work has never been warmer and more accessible.

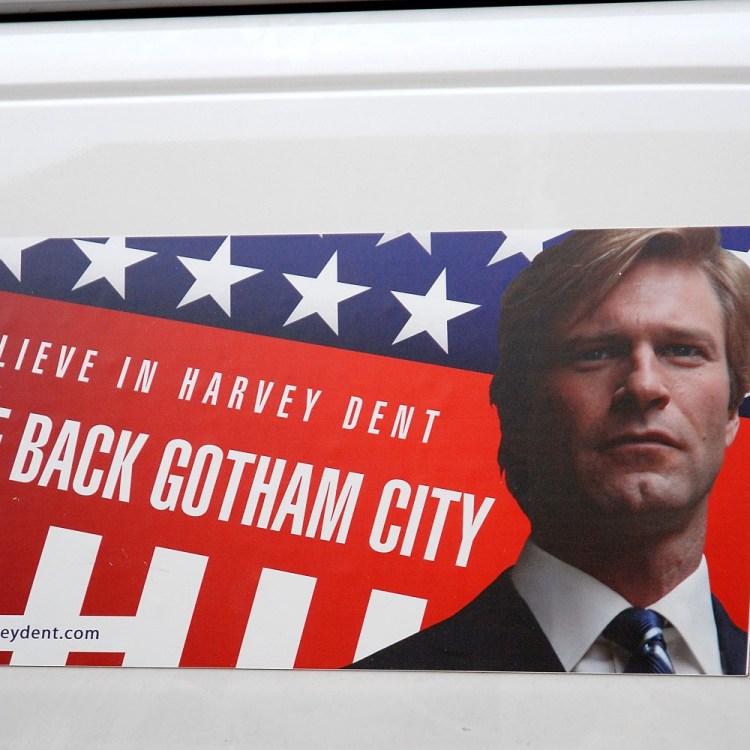

In this heist film that bests the Ocean’s Eight reboot, four Chicago wives played by Viola Davis, Michelle Rodriguez, Elizabeth Debicki and Carrie Coon find themselves maximally screwed. During a botched getaway, their thieving husbands explode in a van with the loot. In order to service their spouses’ debt, these strangers have to pull together and pull a heist themselves, using a roadmap left by the group’s leader, Harry Rawlings (Liam Neeson).

In other words, the widows woman up.

And, in a way, that’s what’s happening to McQueen. Having shed the burden of masculine achievement, gotten his Oscar for 12 Years, made a film about the Irish troubles, contemporary man’s unquenchable desire, and slavery, the married 49-year-old father of two has put his stamp on the kind of crime genre entertainment he loved from his British TV-watching youth in 1983.

The feminine inspiration stems, in part, from Linda LaPlante, who has a “based on” writing credit. The author and screenwriter’s best-known police procedural Prime Suspect starred Helen as D.C.I. Jane Tennison, a brilliant functioning alcoholic with relationship issues, class struggles and difficulty dealing with authority. Before that, LaPlante had a British hit with her two-season ITV crime drama, Widows, which laid down the plot for McQueen’s movie.

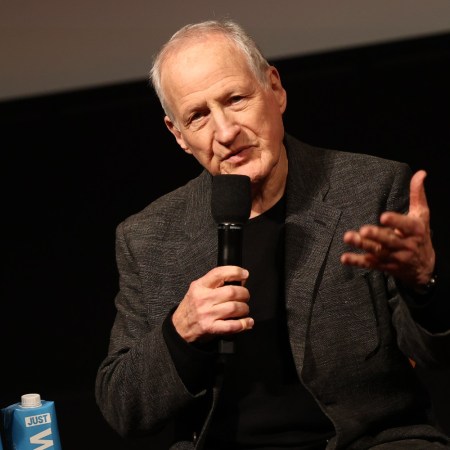

“I identified with these women,” McQueen recalled at an intimate awards-schmooze lunch at Manhattan’s The Modern. During the event hosted by tastemaker doyenne Peggy Siegal last week, the teddy-bearish director sat down at a table with journalists and film insiders, suggesting that LaPlante empowered female characters usually relegated to the sidelines. McQueen related to these otherwise invisible women as kindred spirits and fellow outsiders. He added: “As a child, I identified with Sean Connery as James Bond, Johnny Weissmuller as Tarzan — and these middle-aged women. Their journey putting the stereotype on its head stayed with me for 35 years.”

Nowhere is this clearer than in how McQueen shoots intimacy, particularly that between Veronica and Harry Rawlings (Davis and Neeson). Even the conjugal sex scenes are “smooth enough for a woman,” to quote the old razor ad. This has not always been the case with McQueen. Often, sex is fraught and not-so-hot from a female perspective.

In Shame, sex is lust, hold the emotional connection. McQueen’s go-to actor Fassbender has graphic anonymous sex against the windows of his high-rise hotel. And as steamy as the action is, the gaze is frigid.

Playing his sister, co-star Carey Mulligan appears naked too. I felt sorry for the BBC beauty baring her breasts for the first time. It wasn’t just that, as I wrote on the Huffington Post at the time, “[A] ll the fuss seemed to be about her co-star Michael Fassbender baring his junk, swinging the thing like a patrolman with a billy club.” It was that she stripped naked only to exist as a mirror for Fassbender’s loner to see himself – a lost white chick whose character develops from A to B even as Mulligan gut-wrenchingly travels to Z.

While12 Years a Slave made Lupita Nyong’o a star, earning her the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, she plays a character that by definition lacks agency. Her slave Patsey is raped by master Edwin Epps (Fassbender), which, unsurprisingly, is as disturbing as any horror movie exploitation trope. Patsey doesn’t own her body – and in that way she’s no different from every rape victim. And she doesn’t carry the narrative, which makes her a typical character in the McQueen film universe.

Until now.

With Widows, McQueen shifts gears. Not only does he worship his lead actress, Davis, but there’s a new potency and equality to the intercourse between sexes. At the lunch, McQueen said of Davis that she is “one of the greatest actors of her generation. She could do an underwater musical. I want to see a Viola catalog.”

McQueen shoots Davis almost as if she were Elizabeth Taylor; she is magnificent, monumental. And just that is a radical act, even for the filmmaker. She gets the Fassbender treatment.

In a fresh-out-of-bed scene, Veronica joins her naked husband in the bathroom. Bathed in brilliant morning light, they share a shot from Harry’s ubiquitous silver flask. Her desire and his virility bounce off the white tile. McQueen has created a scene that is sexy for men and women in a Liz Taylor-Richard Burton way that crackles and informs all the couple’s scenes together.

Even in 2018, there’s something bold and transgressive about the power of their nudity and marital intimacy – they’re dark and pale, female and male, a study in contrast. And this is McQueen using action and character to embody a statement of inclusion and equality, however fleeting, a momentary balance of power, a truce in the ongoing war between men and women, black and white.

“Love is political regardless of who you are with,” McQueen said later that night following a MOMA Contenders screening of Widows.

With this genre crowd-pleaser, McQueen continues to explore his central concerns: race, class, politics, inequality, violence and corruption. And yet this looser, warmer gaze suits his themes, too. It is possible that by expanding the circle of women in his work, the already accomplished McQueen liberated himself, too.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.