Hanukkah is a festival of lights, a holiday for remembering a people’s fiery resolve and celebrating their battle against the darkness.

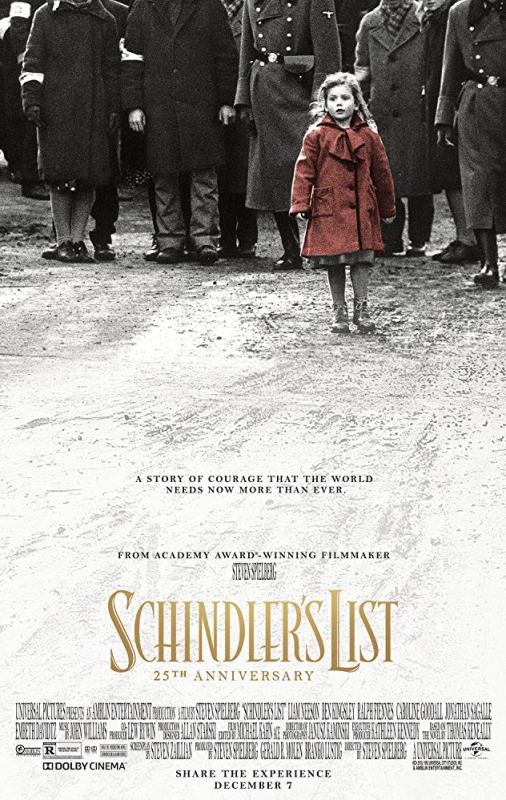

Which makes this week a good time for the reissue of Steven Spielberg’s epic of tragic history and unexpected heroism, “Schindler’s List.”

Honoring the classic’s 25th anniversary, Universal Studios will be hosting free screenings for high schools on December 4th and 5th;, and bringing the digitally remastered movie back to theaters on December 7th. A re-release on home-entertainment platforms, and to international markets, follows.

To watch the film again, after a quarter of a century, is to recall its meticulous artistry, and its painful power. To be reminded, again, of the bigotry and hatred still around us.

And to see how much further we, and the movies, still need to go.

In 1993, the film was a personal breakthrough for Spielberg, who long had been fascinated by Oskar Schindler — and terrified of telling his story. The director’s earlier adaptation of “The Color Purple” had engendered some controversy; his “Empire of the Sun” had failed to find any audience at all.

This project was an even more daunting challenge, and for years Spielberg tried to persuade other directors to take it on.

But as he watched the rise of hate groups and Holocaust deniers in the early 1990s, Spielberg realized this wasn’t a movie but a personal responsibility. He needed to make it himself, no matter what it took, or took out of him.

So to convince Universal to fund it, he shot the blockbuster “Jurassic Park” for them first. When they brought up the question of his fee, he declined one. Taking a salary for shooting this story, he said, would be “blood money.”

It seems almost fatuous now to praise Spielberg’s filmmaking skills – even when his films sometimes slip into sentimentality, his vision is always precise – but at the time, “Schindler’s List” demonstrated an entirely new level of directorial control.

It still impresses.

The use of imagery is masterful. A guttering Shabbat candle turns into a factory chimney (and foreshadows the gruesome exhaust of the crematoria). The bright red of a girl’s coat in a grey ghetto signifies life – and, finally, death.

The casting is brilliant, too. It’s not just the performance themselves – Liam Neeson getting the Aryan arrogance of Schindler in the tilt of his head, Ralph Fiennes recreating the soulless eyes of camp commandant Amon Gőth. It’s the way the two actors mirror each other.

They are both big, handsome, hawk-nosed men. They enjoy strong drink and pretty women. They trade favors and share jokes. Gőth isn’t a bad man, Schindler tries to argue once, vainly. It’s just this stupid war, he insists. It “brings out the worst” in people.

And that is perhaps the most devastating message of “Schindler’s List” – how close we are, all of us, to being evil, or at least to excusing it. How little it takes to sway us, either way.

It’s sadly, a message that needs repeating today.

Recently we’ve seen young, clean-cut men shouting Nazi slogans in Virginia. A bloody massacre in a Pittsburgh synagogue. A Jewish professor’s office at Columbia University vandalized with swastikas and slurs. Similar graffiti turning up in California and New Jersey.

Bigotry is on the rise.

And yet Hollywood movies have rarely risen up and truly confronted it.

Although “Schindler’s List” is an undisputed classic, it unconsciously incorporated some of the industry’s oldest approaches to telling a story about bigotry — and the very fact that the film succeeded, so brilliantly, has only encouraged far less gifted filmmakers to continue to copy them, awkwardly.

The cinematic rules are simple, and safe. The tales are told, not from the point of view of the victimized minority, but of someone not like them – someone like “us.” A privileged member of the majority, our hero grows righteously appalled at the injustice around him, and becomes the unexpected savior of a powerless, persecuted people.

There’s nothing inherently wrong in that story; it is, in fact, Schindler’s own, and the basis of the novel, “Schindler’s Ark,” that the screenwriter worked from.

But what if this tale had been told, not from Schindler’s point of view, but from that of Itzhak Stern, the Jewish accountant who actually devised the plan to save the Jews? What if Spielberg had decided to make a movie, not about the destruction of the Kraków ghetto, but about the defense of the Warsaw one, in which Jews rose up and waged war against their oppressors?

It would be a different movie, to be sure, but perhaps an even more inspiring one.

Since the success of “Schindler’s,” films about bigotry and genocide almost invariably copy its structure. Only a few movies – 2008’s “Defiance,” about the Jewish partisans of World War II, 2016’s “The Birth of a Nation,” about Nat Turner’s 19th-century slave rebellion – show an oppressed people fighting back. Most prefer, again, to see them only as victims – pained, patient, passive – waiting for help.

And while, yes, these are often the facts of history, too often movies about prejudice see it only as history.

Just this year, “Green Book” (in which a white man helps a black one reconnect with his own culture) was set in the early ’60s. “BlacKkKlansman (in which a white cop infiltrates the Klan chapter his black partner obviously cannot) is set in the early `70s. Other recent films about prejudice – “Where Hands Touch,” “The Zookeeper’s Wife,” “Detroit,” “Hidden Figures,” “The Help” – remain safely placed in the past as well.

And the problem is that implies that’s what bigotry is, too – history. Something that happened, once, in small towns, or other countries. Something we solved for “them,” and for which they should be grateful.

Which isn’t to say there shouldn’t be movies about the Holocaust (particularly when so many irrational racists still try to minimize it). Or movies about the Civil Rights era (especially when so many current legislators, with their attacks on voting rights, seem to be in a hurry to erase its victories). Many of these films are based on real people, and real events.

But too often these period pieces are the only ones that get promoted, while other, more relevant, truly empowering movies have to fight even to get seen. Like this year’s “The Hate U Give,” which invokes the Black Lives Matter movement. Or “Blindspotting” and “Sorry to Bother You,” which look at all the assumptions and attitudes that still divide us.

And that’s a shame because, as good as they might be, movies about bigotry in the `60s, or anti-Semitism in the ’40s, only make it easier for us to think it isn’t a problem now. Just as every movie that features a Christian hero standing up for the Jews or a white boss defending his black workers – even as their stories emphasize solidarity – almost encourages victimhood.

It turns the real subjects of these stories into supporting players. It robs them of their own agency.

This is a good time, to be sure, to take another look at the artistic achievements of “Schindler’s List” – to marvel at Janusz Kamiński’s silvery black-and-white photography, to weep along with John Williams’ sobbing score, and to praise Steven Spielberg for so brilliantly bringing it all together.

But it’s an even better time to look around at where we are now – and look to other filmmakers to tell new, uncomfortable, uncompromising stories about where we need to go.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.