Just two days before Thanksgiving 1968, Air Force helicopter pilot James Fleming gave six desperate Green Berets fighting in the Vietnam War something for which to be eternally thankful.

On the morning of November 26, First Lieutenant Fleming was tasked with piloting a UH-1F “Huey” helicopter to insert a seven-man Special Forces recon team into a “hot” area along Cambodian border so they could embark upon an intelligence-gathering mission.

Before missions like the one he flew on November 26th took off, Fleming said the men would often link arms and communicate, even though few words were exchanged.

“It was a way of saying ‘I’m gonna take you and I’m going to put you out in the middle of hell. And if you have to come home, I’ll bring you home,’” he explained. “I’m telling him that. That’s my duty; it’s my honor. That’s what I do.”

And, though things did not go as planned, that’s exactly what he did.

While conducting reconnaissance in the area, the Special Forces team was discovered and ambushed by a large enemy force of North Vietnamese soldiers. As the firefight raged, the outnumbered team of Americans retreated as best they could to a river on the border of Cambodia and Vietnam.

Outgunned and pinned down, the team set up a defensive position with the water at their backs and sent out an emergency call for an immediate extraction.

That frantic call was relayed to Fleming and four other aircraft—two of them helicopter gunships—and all five converged on the area despite being low on fuel reserves.

Upon arrival, one of the gunships was downed almost immediately by heavy fire and another of the choppers was then diverted to rescue that crew and return them to base. A third chopper quickly burned through its fuel and also had to retreat from the area, leaving only the remaining gunship and the UH-1F being piloted by Lt. James Fleming to attempt the rescue of the Green Berets.

And attempt it they did. “I hit that riverbank and my right door gunner starts shooting,” Fleming said. “We’re starting to take damage and starting to take rounds. All of a sudden, the radio operator says ‘Get out, get out, they got us, get out!’ I hear that and we’re taking damage so I put the nose down and go down the river and leave the area.”

From this fresh vantage point, however, Fleming could see the enemy had locked in on the Americans, forcing the small team to blow the claymore mines they had scattered around their position as a last line of defense.

Despite the enemy closing in, Fleming saw an opportunity to try to swoop in once again using the dust in the air raised by the exploded mines to screen his movement. To aid the rescue, the remaining gunship on station made one more strafing pass with its guns to drive back the North Vietnamese.

“I hit the riverbank again and we’re doing the same operation,” Fleming said. “As we get further down, we’re starting to take some pretty good damage. My door gunner was shooting and yelling.”

In an exposed position and dangerously low on fuel, Lt. Fleming kept the chopper in place as hostile fire crashed through his windscreen and members of the patrol team boarded the chopper.

Thanks to Lt. Fleming’s bravery, six of the seven members of the Special Forces team made it safely onto the chopper before it departed, one of the Green Berets held on to the Huey’s landing skid as it lifted off to leave.

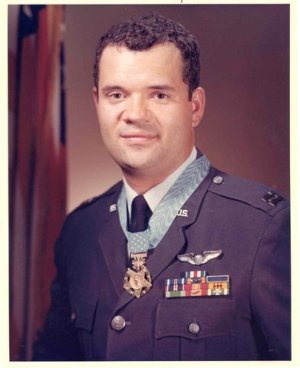

For his heroism under fire, Lt. Fleming was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Nixon at the White House on May 14, 1970. During the ceremony, Nixon told the honorees, “Today is not my day. It’s your day.”

Reflecting on his heroics and the award afterward, Lt. Fleming said: “How many helicopter pilots were in Vietnam, thousands? How many pilots did what I did and got shot down and died and no one saw it, hundreds? I know that. I was recognized. I owe a lot to those that weren’t.”

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Lieutenant Fleming was also awarded the Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Meritorious Service Medal, Combat Readiness Medal and numerous other commendations for his service.

Fleming was also promoted to the rank of Captain.

A portion of his Medal of Honor citation reads as follows: “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Capt. Fleming (then 1st Lt.) distinguished himself as the Aircraft Commander of a UH-1F transport Helicopter. Capt. Fleming’s profound concern for his fellow men, and at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Air Force and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country.”

Fleming, the Medal of Honor winner, remained in the Air Force and rose to the rank of Colonel, eventually retiring from the service in 1996.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.