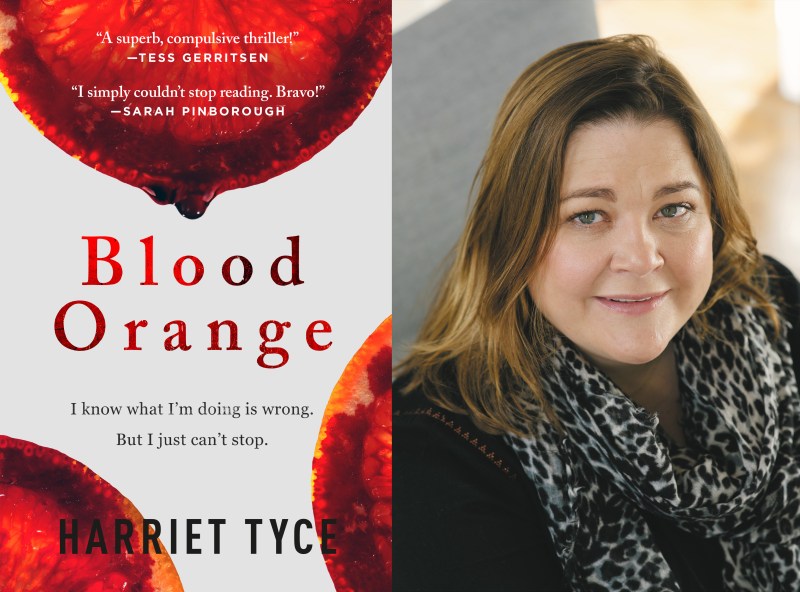

Welcome to Chapter One, RealClearLife’s conversation with debut authors about their new books, the people, places, and moments that inspired them, and what makes their literary hearts sing.

There might not be a single person in debut author Harriet Tyce’s Blood Orange who isn’t morally corrupted and heavily flawed. But like the many segments of a certain piece of fruit that plays an unexpectedly pivotal role in her book, Tyce’s characters are multi-dimensional. Just when you think you’ve got them pegged, a new aspect of their personalities — sometimes influenced by way too much drinking or something they weren’t even aware they were slipped — takes over and reveals something darker. Take Alison. Sure, she’s cheating on her husband and choosing to spend time with her lover over her daughter and preparing herself to risk her law career by lying to the court, but she’s got a lot going on. She’s the breadwinner in her marriage and her husband, a sex therapist, doesn’t even try to hide his contempt for her. Her pseudo-boyfriend has rather aggressive tendencies and she’s not altogether convinced that her client is guilty of the murder she’s readily admitting to. But only one of these people is actually lying, the rest have shown who they really are repeatedly. It’s up to her to believe them.

RealClearLife: Can you talk a little bit about what got you into writing a thriller to begin with? Are there authors or other works that inspired Blood Orange?

Harriet Tyce: I’ve always enjoyed reading thrillers and in particular, novels with an edge of psychological suspense. When I started to write, I found that style was the one that came most easily to me. I tried to write a couple of feminist dystopian novels, but they also came out more like psychological suspense, so that was the moment I decided I should pursue it properly. Blood Orange was in part inspired by my own experiences as a criminal barrister — I had ten years of experience, which was the most amazing research and it seemed a shame to waste it. Apple Tree Yard by Louise Doughty was a book that made me think that it might be a topic in which people were interested.

RCL: Your law career felt like it came through in the text and really made all the legalities in the book feel legitimate. Have you ever faced a case like the ones you wrote about?

HT: Not personally, no, because my practice was very junior even at the point at which I stopped working as a barrister, and I wasn’t dealing with offenses that were this serious. I did however work on the papers for murder trials and serious sexual offences for various pupil supervisors when I was in training. And regardless of the nature of the offense, the way that a trial runs is always the same, so I was familiar with the framework within which I had to operate.

In terms of the case of Madeleine Smith, it’s a murder trial but in the context of domestic violence. The ‘battered woman syndrome’ defense to murder is one that until recently did not fit neatly into the legal structure of defenses to murder, which did not allow for a slow burn provocation of the sort that manifests in an abusive scenario. There is a pivotal case in English case law called R v. Ahluwalia, which involved a woman who burned her husband to death in 1989. She claimed it was in response to ten years of serious domestic abuse, but she was initially convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. The conviction was later overturned. The loss of control defense to which I refer in Blood Orange was introduced in part due to the outcry surrounding this case and others. The injustice of it struck me heavily when I was studying law in the first place, and I was always interested to explore those themes further.

RCL: Not to pry, hopefully, but you write with such clarity and in such detail about these varying tumultuous relationships — are you drawing from personal experiences at all here or are they each imagined?

HT: Ha! Well, I have done what all writers do, I think, and taken small pieces of my own experience here and there and spun them up into a completely different narrative — my husband always says I have a very active imagination. I am a wife and a mother and have had some bad relationships in the past, and also have listened to friends and family talk about all their bad experiences — there’s no shortage of material in life when it comes to the complexity of relationships.

RCL: Did you always want to write a book during your law career? Do you have a background in literary fiction at all?

HT: My first degree was a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature at the University of Oxford so I do have a background in literary criticism of classic texts. While I was a barrister I was too busy dealing with work to think about writing, though I have always read constantly. It really was something that came more to me later, in my thirties, after I had children.

RCL: There seems to be a trend in the past few years of women writing thrillers that star other women who are unreliable narrators — like Gillian Flynn, Paula Hawkins, Tana French — is this something you drew from? Do you find Alison’s flaws and general unreliability to be relatable and even endearing?

HT: I’m extremely fond of Alison, personally, though I accept that I am extremely biased. And I don’t see her myself as being an unreliable narrator — to me, those are narrators who are deliberately withholding a crucial piece of information from the reader. She is unreliable but only to the extent that what she thinks is happening, is not the real situation. When it came to writing her, I was very keen to create a fully rounded, three-dimensional character, with flaws but also with redeeming features. Female characters who transgress tend to be treated very harshly in psychological thrillers and I felt, to me, it was very important to try and subvert that; to have a female protagonist who has voice and agency and is complete in her flaws as well as her strong points. From readers’ responses so far, the majority view is that they develop sympathy for her as the story progresses, and this is very pleasing as it’s what I hoped would happen.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.