What is a young adult novel?

“It’s a good question,” Derek Milman says when asked to define the genre. The basic definition is simple: It’s typically a book with a young central character that is, at least theoretically, aimed at young readers.

Except when it isn’t: “Some books do skirt that line.”

He cites Emma Cline’s 2016 debut novel The Girls: “That’s technically a YA book but it was marketed as literary fiction.” (Its central character is a teenager, but it follows her as she meets up with Charles Manson.)

Growing up, Milman recalls one side of the divide being far more appealing than the other. He felt young adult novels were something to be avoided, recalling the “cheesy-looking books in this really tiny section of my library” and seeking more mature reading material.

Now? “There’s definitely a lot of adults who read YA.”

Indeed, there are massive numbers of YA readers. Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series sold over 100 million books and its film adaptations racked up more than $3.3 billion worldwide. (It also inspired another publishing sensation and then film franchise, albeit one aimed at adult adults: 50 Shades of Grey.)

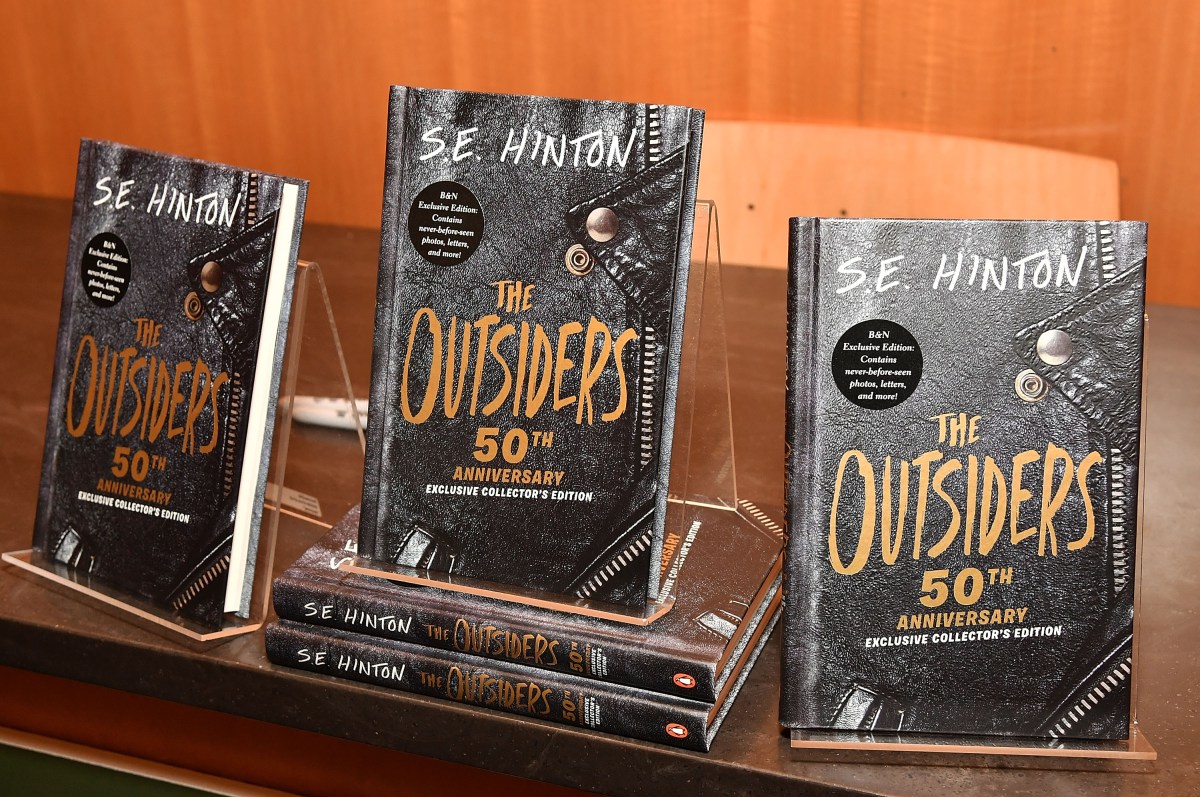

Twilight was Meyer’s first published novel. (Much as The Outsiders was S.E. Hinton’s, Harry Potter Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was J.K. Rowling’s and To Kill a Mockingbird was Harper Lee’s.)

Obviously, successes of this magnitude are absurdly rare…but when lightning does strike, it tends to happen with YA novels. Witness Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series.

Collins is also representative of the fact that women largely dominate the YA genre. “I’m in a debut group and out of 200 people, I’m one of maybe 15, 20 guys,” Milman says. He doesn’t have a concrete answer for the gender disparity, but speculates: “I think part of it is that girls tend to read more than boys.” Of course, YA books don’t only appeal to girls nor are the successes exclusively female. (Witness The Fault in Our Stars author John Green.) But no one should be surprised that women excel at producing books that come from what Milman calls a “place of truth” and resonate with young female readers. Nor should it be a stunner publishers find this appealing.

To dig into how YA novels go from an author’s mind to the bookshelf, RealClearLife looks at how Milman’s debut, Scream All Night, came to be. (This is not to say those looking to get published will have the same experience—like any great story, publishing has a knack for strange twists.)

The Beginning. “I just had an idea of a kid who inherited a horror movie studio,” Milman recalls. It first occurred to him “many, many years ago,” but he didn’t have time to explore it because of his chosen profession: acting.

The Motivation. One of Milman’s favorite memories of his acting career also illustrates why he wound up writing. He got a call about a new job: “I would have to improvise with Leonardo DiCaprio in 48 hours.” Not only that, but he would have to do it in a New Zealand accent. (His agent had already assured Martin Scorsese this was something he could handle.)

Frantic, Milman tried to avoid “sounding Australian” as much as possible for the 14-hour shoot of what turned out to be the final scene of 2013’s The Wolf of Wall Street. (He’s one of the Kiwis attempting to sell DiCaprio a pen.)

Milman recalls there being “400 extras behind me” and generally having a wonderful time: “Both Scorsese and DiCaprio were really warm, personable people.”

This was also reflective of his dissatisfaction with the profession. Milman had already auditioned for the film “like a million times for all kinds of roles.” (Having seen the finished product, Milman suspects he may have lost out on bigger parts because he “didn’t come off as enough of a douchebag.”) His hiring came so late in the process that he’d mentally moved on: “I totally forgot that movie existed.”

Even a great experience couldn’t fully distract Milman from a deeper frustration. He was fed up with the feeling of being “perpetually not in control.” (He would suddenly hear he was a leading contender for a role in The Hobbit or another project that could change his life overnight, only to have the part slip away just as abruptly and mysteriously.)

With writing, it was different: “I’m in control of this. This is mine whatever happens.”

Take One. “Around 2012, 2013, I wound up writing my first young adult manuscript, which was this horror/sci-fi mash-up.” A friend liked it enough to take it to some publishers: “Harper Collins got interested and an editor took me under their wing and that’s how I got my first agent.”

The Agent Arrives. Representation entered the picture at the end of 2014: “My agent emailed me a whole set of notes. We spent several months getting [the manuscript] in shape.” Finally a sale happened… almost. “Harper Collins and Penguin tried to buy it, but it got shot down at acquisitions.”

Take Two. “When you submit a manuscript and when there’s interest and you get an agent, people are like, ‘What else are you working on?’” Spurred on by the inquiries, Milman began to flesh out that old idea and started his second manuscript, Scream All Night.

Acquired. Again publishers were contacted. In the spring of 2016, success: “I got a double offer from Harper Collins, which meant I was able to choose my imprint and editor.”

Announced. This information wasn’t shared with the world just yet: “We didn’t announce it for another seven months.” This proved consistent with the slow road to publication: “[Publishing] Scream was a drawn out process. Not that the editing necessarily took that long. It was the waiting in between.”

The Big Picture: “I got an editorial letter from my editor, which was an overview of broad stroke changes that they want.” Milman says it was fairly short—“I think it was just two or three pages”—and gave guidance on how they wanted to “sculpt” the manuscript. “That took three months.”

The Specific Stuff: “Those were more line-by-line notes,” Milman says. This could be grueling: “I found that to be the most challenging phase, because you could spend nine hours on a single page. On a single paragraph.”

The Sensitivity Read: In Scream All Night, the main character’s mother is schizophrenic. Two sensitivity readers who had experience with mental illness were brought in: “The publisher suggested it, arranged it and paid for it.” Milman is grateful they were part of the process: “They really added depth to the character and the story.” (Notes were typically less don’t write that than pointing out a “need to create a little bit more of a story in terms of the character’s delusions.”) A professor from Brown also served as a reader, leading to moments when all three had a different opinion on, say, a word choice. (At which point Milman tried to “be as truthful as I can” and reach the decision on his own.)

These two stages took “maybe a month or two.”

Some More Specific Stuff: “There was another batch of line note revisions,” Milman recalls. “At that point my editor left for a different job.” This was unnerving, as a new editor could have a profoundly different take on the book than their predecessor. Milman says it worked out surprisingly well, with the publisher doing “what they could to make it a very smooth transition.” (Not everyone is so lucky, as will be explained.)

Everybody Chimes In. After a “couple months,” an electronic document arrived, filled with input from all sorts of people. “There are comment bubbles from your editor, the copy editor, another copy editor, all these people responding.” This phase proved both relatively brief (“Like a week and that was done”) and surprisingly enjoyable (“I actually found that really fun”).

A Preview of the Final Product. In the “late summer, early fall” of 2017, the advance reader copies arrived. ARCs are “paperback versions of what the book is going to be, but it’s still uncorrected.” These “go out to reviewers, newspapers, magazines and a lot of bloggers.”

(Advance notices can be a reminder that we live in highly aware times. A generally positive Kirkus Review of Milman’s book includes the observation: “Most characters are presumed white, but there is a diversity in age and socio-economic status.”)

At last the finish line was visible…but it was only a hazy vision in the distance because there were three more passes to go.

Pass #1. Around December, Milman received the “giant stack of pages” making up the book. They came with a new set of comments from the publisher he needed to address by hand in the margin. In particular, this pass was filled with resolving “little things with the timeline” as well as random details that suddenly needed to be addressed, such as determining how to best describe removing boxing gloves.

Pass #2. Having gone through this meticulous editing process once, the second time was easier. (“There was less stuff.”) Even so, there remained an awareness that any change can alter not just that page but the rest of the work as well: “Ripple effects are terrifying.” Quite simply, the small alteration can have major, unintended continuity implications. (“If I take one word out, is he suddenly going to be an android?”)

Pass #3: “The third pass was more technical: Can we close the space here? Can we do something with this font?”

This is also when it became nearly impossible to see the book with anything approaching “fresh eyes” and Scream All Night finally broke him: “I can’t read the book again. The third pass, I went, Okay, I’m reading the book one more time…”

And at last…

Publication! (At Some Point!) Scream All Night was supposed to be out by now. But it is not. “It got pushed two months,” Milman explains.

While Milman doesn’t know the exact reasons for the delay, he isn’t particularly surprised by it: “It happens.” Indeed, he knows someone whose book just came out and was originally announced back in 2014.

Four years ago? While such delays are fairly common in Hollywood—Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret with Anna Paquin and Matt Damon underwent a six-year legal battle—why with a novel?

“An editor could leave. A marketing thing. They have too many books coming out at that time. Who knows? That gets filed under the mysteries of publishing, which is a very large file.”

Meanwhile the next one currently moves forward at a much faster rate: “My second book is coming out from the JIMMY Patterson imprint at Little, Brown.” (It’s the personal imprint of the absurdly prolific crime novelist and children’s author James Patterson.) “That’s scheduled for spring 2019 and I haven’t even started editing that yet.”

Scream All Night will be published on July 24. (At least, that’s the current plan.) You can order a copy here.

It will be a great day for Milman, provided no one expects him actually to read it: “I really can’t do it again.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.