A tough day on the job for the average citizen: snarled traffic, meetings that redefine boredom, stressful negotiations over email or possibly even some physical labor. All definitely warranting of a glass of rosé or a beer if you fancy.

Tough day on the job for a not so average citizen: seven hours of sitting in a bone-chilling -10C to photograph one of the planet’s most elusive animals making a kill. Now, to make it even less ordinary, extend that assignment to a camping trip and 17 days without a shower…for comparison’s sake, refrigerated milk goes bad after 15 days…all for the creative pursuit of documenting the essence of a place and the wild beasts that call it home so the rest of us can experience its magnificence without risk of toes blackened by frostbite. Shackleton would be impressed…and would no doubt toast to this with a stiff glass of whiskey. Rosé doesn’t seem his style.

Inger Vandyke is a wildlife photographer, conservationist and expedition leader. Trekking to the far corners of the world to connect with sentient life is rooted deep in her DNA.

She grew up on a fishing trawler on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, followed her passion into photography, led her first expedition into the Himalayas in Nepal at the age of 24 and started regularly leading her own expeditions well before her 30th birthday. She’s been through 4×4 training, can captain a boat and is a certified rescue scuba diver. All skills that have helped her navigate the challenges of global exploration in pursuit of extraordinary subjects.

She also happens to be the first woman to photograph a snow leopard hunt in the wild…in the aforementioned camping trip on ice. This puts her in a category of humans whose repertoire of experiences is limited to a small group of life club members with more fire in their core than some active volcanos.

Life clubs are collections of experiences that define who we are…and we share an overlap in those clubs with like-minded souls who have dipped their toes in our chosen vocations or avocations. Marathoners, firemen, urchin divers. Some clubs are decidedly more desolate than others.

Having polar bears breathe on your face for instance, or feeling a whale song reverberating throughout your entire body are two clubs whose membership could be considered platinum.

Inger’s work often moves her to tears and the connection she feels to her subjects fuels the passion with which she imbues every image of her work.

Her views on humanity are more forgiving than one might expect from someone who has seen both the beauty and the devastation of the human condition and the way with which we treat our planet and its other inhabitants. “I’ve always seen people as vital to conservation, not always as an opposing force to it,” she says….possibly giving us more credit than we deserve. Yet that devotion to finding the best in people, in places, in moments…the act of documenting our similarities rather than our differences…is what allows Inger’s work to tap into the emotional epicenter of her audience.

Passion is a powerful driving force for people. How did yours develop and mold who you are and what you do?

Inger Vandyke: My mother likes to tell a story about the first steps I ever took. She said that I used her dress to climb to my feet and just walked away on my own. I guess I’ve always been an exploring person. I like the road less traveled and remote places. I was blessed to have parents who raised me with a healthy sense of place and people. They never taught me to mistrust strangers. Instead they taught me to half trust and to treat people as genuine until proven otherwise. These core beliefs have underpinned my experiences throughout my entire life. I love everything about wild places – the landscapes, wildlife and people that live in them. I was raised on a fishing trawler, so I never feared the ocean or being outside, sleeping under the stars. It made me a creature of the outdoors. I don’t cope well with long periods inside.

When I started traveling in my early twenties the first adventurous place I visited was the Sahara. While I was traveling there, I mostly fell in love with the people, the wildness of it and the silence. Since that time I have been blessed to return to the Sahara several times and I’m still beguiled by that part of Africa. But I have been lucky enough to work with indigenous people in Australia, Tibet, India, the Arctic and in southern Africa. I’ve always felt connected with people whose lives are determined by the movements of the wind and sea, by people who are connected to the earth. I’ve been fortunate enough to spend time gathering food with Wik women in western Cape York in Australia, drink tea with nomadic Tibetan shepherds in remote western Tibet, sleep on the floor of a Tuareg family kitchen and sit in the dirt with Himba women talking to them through translators.

While I began my photographic career in conservation of wildlife (and I still do a lot of conservation photography), I’ve always seen people as vital to conservation, not always as an opposing force to it.

You grew up on a fishing trawler! What an absolutely magical experience for a child. What were the key moments of that lifestyle that you now know set you on your path?

IV: My childhood was highly unusual. I think my brother and I share this childhood with only a small handful of other kids whose parents ran working fishing trawlers in Australia. I effectively grew up on the Great Barrier Reef and my days off were spent watching sea turtles nesting, swimming with Manta Rays and looking at nesting seabirds on remote islands.

I remember when I was around eight years old, my dad told us to batten down the hatches and get all loose items off the deck as a big storm was coming. It was around 8 p.m. and although I couldn’t see the storm, I felt the wind building quickly. We pulled up anchor and moved away from the reef to escape any danger or being run on to the reef. My dad and I worked through the night to drive our boat to a sheltering place where we could escape the worst of it. We went with the winds and arrived at an island over 150 kilometers away at sunrise when it was nearly over. I think if there was a pivotal moment of my childhood that defined who I am today that was one of the main events. Even today I am usually very level-headed in a crisis and I tend to be systematic in the face of issues, rather than someone who panics.

You were the first woman to photograph a snow leopard hunt in the wild. They are such elusive animals! Describe the experience of that shoot and the feeling of being labeled “the first” at something so special.

IV: I first went to photograph Snow Leopards in Ladakh in 2014 but we were there a little late in the season. Although we saw Snow Leopards during that initial trip, they were distant and shy. So we decided to return to lead the Wild Images Snow Leopard Expedition in 2015 and my partner, Mark Beaman and I went with two separate groups to the mountains for 20 days. During those two trips, which were timed to take place in the pit of the Himalayan winter at the end of February, we went for the whole time without showers. We were camped out in-25C temperatures at night. By day the temperatures averaged-10C. During the course of three weeks in the mountains, we were blessed with a number of close encounters with Snow Leopards but the true highlight was spending a whole afternoon with an older male we’d been tracking for a few days. We saw him wandering down a valley, so we stopped, found a place to hide and watch him. He spent most of the afternoon resting until close to sunset when he spied a herd of Blue Sheep. He tried to hunt for one of them right in front of us! Although he wasn’t successful, I remember crying when it was over. We had just witnessed something so incredibly rare and I became the first photographer in the world to capture a wild snow leopard hunt from start to finish in photos. It was something I will remember for the rest of my life. The hardships of the cold, lack of showers, altitude, the fact my fingers were bleeding from scrambling up icy stones and I had frost-burn on my cheek from where my LCD screen on my camera froze to my face during use, the pre-dawn to post-dusk searches – all of that was lost after watching that hunt. I would do it all again tomorrow if I had the chance.

A lot of photographers believe their subjects and the perfect moments find them more than vice versa. How much of your photography is orchestrated by those unexpected moments?

IV: I think that my photography is a mix of different dynamics that varies from image to image. I work a lot outside and I’ve always felt that I’ve managed to get good images simply by taking the time and having the fortune to simply be in the right place at the right time. Like most creative people, I have good days and bad days with photography. Some days where it just comes to me and everything is great. Other days where I’m really not in the mind space for it. I’ve learned to not fight the off days. If it’s not happening for me, and I’ve forced it, then I have been uncomfortable with the way an image has turned out. Elizabeth Gilbert once described the urge to write as a spirit running over the countryside that you need to catch. Once you’ve caught it, it’s best to use it and produce. But if you can’t catch it, then there’s no point chasing it. Photography is similar. Rather than it being my job, it is my journey of wonder, opportunities, inspiration, light, form and place.

What affects you most about the subjects you photograph?

IV: I value all sentient life. All of it. Even animals, places and people that others would write off. I have been moved to tears photographing a bird that represents the last of its kind on a remote island or working in Indian slums that teem with people. Photography is a highly emotional pre-occupation for me and sometimes I don’t quite understand the greater impact of my work. In April 2017 I was blessed to spend two days working in one of Delhi’s most iconic slums. Kathputli was as much a colony of artists and street performers as it was a slum. It was made famous by Salman Rushdie, who wrote about it in his novel “Midnight’s Children.” I loved Kathputli. Its residents hailed mainly from the colorful Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan. Many of them lived in tiny houses, sleeping 8 to a room with poor sanitation. Yet, they were such a close-knit community of people. People who looked out for each other. They welcomed me into their world without judgment or prejudice and to be honest, I actually didn’t have a use for the images I was shooting in Kathputli at the time I went. That is, until November 2017, when the entire community was demolished to make space for a new building. When I heard about the destruction of Kathputli, it moved me to tears. Kathputli was more than just buildings. It was people and for these people, Kathputli was their only home. The colony had existed in its current form for over 70 years. There were people living in Kathputli that only ever knew Kathputli. I donated my images to people who were working so hard on the ground to find new homes for Kathputli’s residents at the start of a very hard Delhi winter. I’m happy to say that around 90% of the community now has at least some form of temporary shelter and my work helped them to get that shelter. I can’t fight every battle that I’m invited to but Kathputli made me realize that my work sometimes has an impact that reaches far beyond my initial expectations. I still think of the people of Kathputli every day. Although I would never have been able to stop the destruction of their homes, I could at least, help them find shelter again.

Can you think of a particularly memorable experience you had photographing animals in the wild and describe it using the five senses?

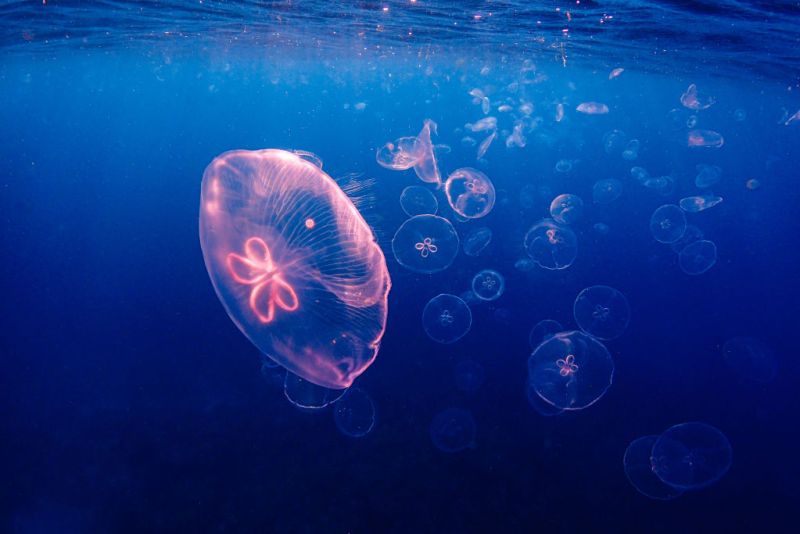

IV: I’ve been blessed to have so many incredible encounters with wild animals over the years. I’ve had polar bears breathe on my face; I’ve stood witness to a wild tiger hunting a spotted deer, the snow leopard hunt, lions hunting zebra in Africa … So many. If one experience affected all of my senses, then swimming with humpback whales in Tonga was probably one of the most memorable experiences of my life. I will never forget the first time I made eye contact with a Humpback Whale in the water. I was in the water with a female Humpback, her calf and an escort. Since I had no idea how fast Humpbacks can swim, I dropped back and had the escort whale track me eye to eye as if to say “I’m watching you. I’m keeping an eye on you with that mother and baby”. I was entranced. It was amazing. Before I swam with humpbacks, I’d seen thousands of them at sea over the years. I’ve always enjoyed seeing Humpbacks and any whales for that matter at sea. Getting in the water with them, however, is an entirely different experience altogether. Humpbacks are incredibly engaging animals in the water. They are acutely aware of your presence in the water with them. Over the course of two weeks I had the privilege of touching the shed skin of a whale after it had been sloughed into the water on a breach, I could smell them breathing behind the boat, taste the salt water on my skin from spending every day in the water with them but the high point was actually swimming with a “Singer” or large male Humpback singing to attract a mate. We crept slowly into the water when we heard the song of a Humpback through the hollows of our boat. Upon entering the water, his song was so incredibly loud! What I never expected, though, was the way his song vibrated through my entire body. We floated in the water directly above this large male Humpback with his fluke down, back arched and singing. From our position his song reverberated through our entire bodies, making our fingers and toenails tingle, our hearts race and our teeth chatter. It was one of the most extraordinary things I’ve ever experienced with wildlife. Sometimes I can close my eyes and imagine it happen like it was yesterday.

With so many photographers in the world, what is the creative vision you’ve developed over the years that helps you stand out?

IV: I’ve never claimed to be the world’s best photographer, but I am a very good editorial photographer. I am good with telling stories in my images and nearly every photo I publish has a story behind it. These stories often get told in my Facebook posts but I blog about some also and I still write two to three feature stories on wild destinations, critically endangered species or vanishing tribal people per year for commercial publications.

Inger Vandyke was the first female photographer to work on remote Heard Island in Antarctica in 2012. (Inger Vandyke)You are also an expedition leader. What does that entail and how did that organically develop as part of your career?

IV: That is such a loaded question. To be an expedition leader, you have to fundamentally love people and you have to be resourceful. Expeditions are like mini dictatorships, not democracies but the style of a leader should never feel dictatorial. I still like to get feedback from my clients in situations, even though I am charged with making the final decision. I generally lead people in places they would never dream to visit, or are too scared to visit, on their own. They come with me because I have usually been before them and they know that I won’t get them into trouble. Whether I’m leading clients across an icy river, driving them across trackless expanses of desert or showing them wildlife underwater on a dive, my job is to make them feel empowered to do that particular thing, to make them feel safe and bring them home. In the last twelve months, I’ve crossed the highest navigable road in the world during a snowstorm, driven vast expanses of trackless Sahara in 4WDs and helped people to land on extremely rough, steep islands in the middle of the Pacific.

I’ve always loved being outside and sleeping outside. I first fell in love with leading when I led a trek in Nepal in 1994. I had always been the organizer of weekend mountain trips for friends and I just turned into doing it professionally.

Getting the skills needed to lead expeditions was something I did as an interest. I have done formal 4WD training in the Australian Capital Territory, I obtained my small boat license doing volunteer Coast Guard work in Sydney, Australia, I became a rescue scuba diver through diving recreationally at the weekends, I have always been involved with First Aid in my full-time work, I have not only done a lot of solo orienteering using maps and compass (yes I’m old enough to know how to use those things. I pre-date GPS) I’ve taken groups of friends doing the same, I learned how to operate a marine radio during coast guard and two way radios through driving boats as a guide in the southern ocean. I’ve taken groups of people carrying everything they need to survive on their back for days on end into the mountains.

While all of these things can be learned, the ability to lead is a bit of a harder skill to obtain. Foremost you must love people. You have to love them enough to care for them when they are sick, reassure them when they are scared, laugh with them when you or they stumble, be humble enough to stand alongside them during their finest moments without taking any credit for it and also have the skills and knowledge to fix something that goes wrong. It can be one of the toughest yet most rewarding jobs in the world all at once.

What’s it like to be a woman in a relatively male-dominated space? Have you had to work harder to prove yourself?

IV: In the early days of my career in Australia I had some horrendous issues with male photographers and leaders either slanting me directly or indirectly. I could tell you some stories that would make your hair curl. I think it is important to acknowledge the fact that women face a much tougher path into my game than many men. Especially if your chosen workplaces are largely male-dominated like the world’s polar regions or if you decide to drive trucks in Africa as a woman. In Africa, I can count on one hand the number of women I’ve met who drive their own expeditions. There are so few of us that I know nearly all of them. I’ve been meeting more and more girls driving safari trucks which is refreshing and good to see. But when you start putting together big expeditions that take three weeks to a month and you are organizing your truck, your co-driver’s truck and your support vehicle to take a small group of people into places where so few people have been before, then the stakes of the game are much higher. You have to be meticulous, organized, resourceful and happy to roll on your back in the African dust to fix the fuel filter on your car if you’ve broken down because of it.

I really wish more women would get into my job. Women are every bit as capable of leading tough expeditions as men. In some ways, their femininity actually enhances the job rather than detracts from it. Perhaps it’s a motherly instinct in me but I am only happy when my guests are happy, healthy, fed and sleeping comfortably at the end of a long day. The experience my guests are having is really important to me and often surpasses any of my own comforts.

Of all of Africa’s indigenous people, Inger Vandyke’s passion lies with the Himba people of Namibia and Angola. (Inger Vandyke)You’ve spent so much time in some of the planet’s most diverse ecosystems, have you been witness to these places changing over the years?

IV: I’ve been blessed to spend many years and have many repeated visits to parts of the world that are at the coal face of human-induced climate change. The Great Barrier Reef, for example, has changed so much from the days of my childhood. Bleaching episodes are occurring faster than they ever have and the reef’s coral doesn’t always get a chance to recover fully between these episodes. I’ve watched population explosions of King Penguins in the Sub-Antarctic through climate change allowing for longer breeding seasons. I’ve also witnessed the changes in glacier sizes in Tibet. We are in the middle of a period of great change. Issues with over-population and the change in our world due to unprecedented demand on the world’s resources is this generation’s greatest challenge. Every generation has a challenge. It’s time we stood up to the plate and started fixing what we can.

Everyone has a message they put out into the world through their words, actions and lifestyle. What is yours?

IV: We live in an incredible world. A world that is often painted as scary by the media. There has always been a radical disconnect between the way the media portrays a country and the reality on the ground. We are now living in an age where we have so much information available to us and this is almost detrimental to travel. It’s almost as if you can Google anywhere and find a reason not to go. Too much information is not only stopping people from traveling to places that they could go to, it is also harming local economies. The world isn’t (for the most part) the terrifying place that people deem it to be. We live in a world that is filled with vibrant cultures, rituals, wild places, wildlife and extraordinary history. The more you see of the world, the more you realize that most of the people sharing your world are like you – they have the same wants and needs as you do – to make sure they have good health, education, a job and that their children have a roof over their heads, are healthy and have a chance to have a good future. There are far more things that connect us in the world than divide us.

What future life goals do you have? Any big bucket list items, travels, career goals, etc.

IV: I feel blessed that at age 47, I have come to a high point of my career. For me, it is harder to go further than this. I am the only woman in the world running an international photography travel company and I’ve been the first woman working on Heard Island in Antarctica, the first woman to photograph a full Snow Leopard hunt. Career-wise I am at the peak I think?

The wonderful thing about photography is the fact you evolve with it. Over the course of my career, I have learned and changed so much. I am still learning and changing. While I was initially awarded for my work with wildlife and conservation, these days I receive as much recognition for my work with people as I do for my work in nature.

My future aspirations lie in more work with vanishing cultures, photographing endangered species and remote places. I am naturally drawn to places that few people have seen and everything that is in those places. If I could spend the rest of my days following a path less traveled I would be happy. I have just returned from a month-long expedition in Chad which has virtually no tourism. The people of Chad rarely see white people, let alone photographers. In 2016 Chad only had 362 tourists visit the entire country and it is such a shame as the Chadian people are so very friendly and they live in one of the most undiscovered, spectacular countries in Africa. It is places like Chad that set my soul on fire. Across Africa and the rest of the world, the lives of indigenous people are changing at an unprecedented rate and while a lot of the change is good and needed, sadly the change is also coming at the expense of their cultures. I am passionate about the preservation of smaller cultures and languages. Every time I am allowed to bear witness to a traditional custom, rite or even if I am invited to sit and share food or tea with indigenous people I feel truly honored. I hope that my body of work serves as a living reminder of what we once lived with when our world had these cultures and creatures. It is my hope to always tread gently in their world, be welcomed and respected as a photographer that is documenting what is fast disappearing.

Advice for anyone looking to get into wildlife photography? What is a good pro camera for a photographer to invest in?

IV: Spend lots of your time outside. Be curious. Find a group of animals you really, really love and use them as a start point. Do volunteer work with them. Find out what challenges they face. Try to find out from scientists what is going on in their world. Document everything. No photography or writing is ever a waste of time. Learn from your mistakes. Never, ever say no to a good opportunity. You are the sum total of the people you spend time with, choose those people wisely. If you meet a detractor, the best revenge you can have is to persist with your work.

If you are starting out as a photographer and you have a limited budget for your kit, then you are better off buying more expensive lenses than camera bodies. Good glass will serve you well for years, often lasting longer than a few camera bodies.

It is always important to remember that you are a photographer because of the way you see the world, not because of the gear in your hands.

Any questions you wish journalists would ask you?

IV: How do you bridge the different genres you work within photography?

I’ve always tried hard to be a diverse photographer who can work with people, wildlife and landscapes. Sometimes, if you become known for one, it is harder to move into another genre. One of the hardest journeys in photography can involve starting with wildlife and going to humans. You find a lot of photographers can do one and not the other well. With people, photography is always more difficult because you have to seek permission. With wildlife you just take shots. People are people and I take a very friendly, respectful approach to them. After all, I love people as much as wildlife, just differently. It has taken me YEARS to get used to photographing people. This might be hard to believe when you see me working in the field or looking at my photos but even today, I still get nervous photographing some people. Something happens when I’m around them though and often the connection I make with people overrides my fear. I love children and I’ve been blessed to hold lots of little hands, play hopscotch in the dirt and when I’m in remote villages I usually let the kids of the village take my phone around to take photos of their own. I show them how to use the camera app and just let them do their thing. If I’m working in Muslim countries, I wear a hijab along with other women. If I am working around people who are frightened of me doing photography, I instantly make myself appear submissive by either sitting on the ground or kneeling. At the end of the day, I hope my images of people reflect a gentle respect and connection with someone, rather than a shot that has been taken against someone’s will.

Have I ever felt frightened in my work?

Rarely. I think to feel no fear is sociopathic. Everyone has fears and I have mine but I’m often in places where people say “Oh! You’re very brave!” yet I’ve never felt brave. This year will be the 28th year since I first visited Africa. In all those years I’ve had TWO experiences that have made me frightened in the entire continent – and I tend to go to ‘no go’ countries across the Sahel, Sahara and Horn of Africa. Two. I think your fear dissipates the more time you spend in some countries. It’s like having a relationship with that country and its people. West African countries like Senegal provide a classic example. A lot of people avoid countries like Senegal because it is undeveloped, poor and has very little tourism. Many people conflate poverty with crime and I feel this is wrong. A lot of the people in Senegal are poor but this doesn’t make them dangerous, they just have no money. Yet they are too proud to steal, they have incredible culture and music and the food in Senegal is generally very good.

I think one of the reasons I move gently in places where others fear to tread, is the fact I cannot see color. I never see a situation as “me versus them.” I see people as I see myself. I love all people equally, regardless of their skin color, their socio-economic situation, their jobs, where they live…. I also hate seeing people in trouble or sick. On more than one occasion I have been guilty of using up my first aid supplies in my truck because I’ve chanced upon a kid who has an open wound on his leg, or my major bugbear in Africa, a child with flies in its eyes that I’ve helped them to wash clean using soap and water. I can’t help every person that I meet, but I care about people a lot and I can make a small, positive difference to their world if they allow me to.

I hope I can always remain mindful around people instead of fearful.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.